How character creators help us explore gender identity and expression

Ultima Online was the first game I played that used character creators. I could barely contain my enthusiasm: I punched in Dad’s credentials and the list of characters populated. I stared back at the screen, perched, awe-struck in his nicotine-stained desk chair, eyes nearly glazed over with equal parts excitement and expectation. The character selection menu was laid out as a shimmering tablet embossed with gemstones. I hovered over the first option: ‘create character.’ Finally, I had permission to make my own.

When it released in 1997, Ultima Online was revolutionary. The size of its world, the scope of its ambition, and the freedom it gave players were all unparalleled. Not to mention the range of character customization options: even on our grainy monitor, I delighted in flipping back and forth, studying the tiny differences between facial presets. I could color my own outfit. I could choose to be a woman. And there were ten unique hairstyles. Ten! The depth of choice was mind-bending. Growing up young, queer, and uneasy with my identity, diving into Ultima’s character creator felt like a revelation.

“I was a timid kid, and I never would have dreamed of expressing myself in a more feminine way for fear of being bullied or reprised in some way,” said Niamh Williams, a non-binary trans woman whose experience with custom character creation helped her come to terms with her identity. “I think the lack of real life social stakes make games a really inviting environment for personal experimentation.”

So many of the people I spoke to had experiences that echoed Williams. Virtual worlds provided a space where they could author new identities without needing to become attached to them. That lack of permanence grants players control over the distance between themselves and their creation. And it’s interesting that, as the medium has matured, it’s moved away from pre-defined everymen—and they were almost always men—to provide players with more agency over how their avatars are defined.

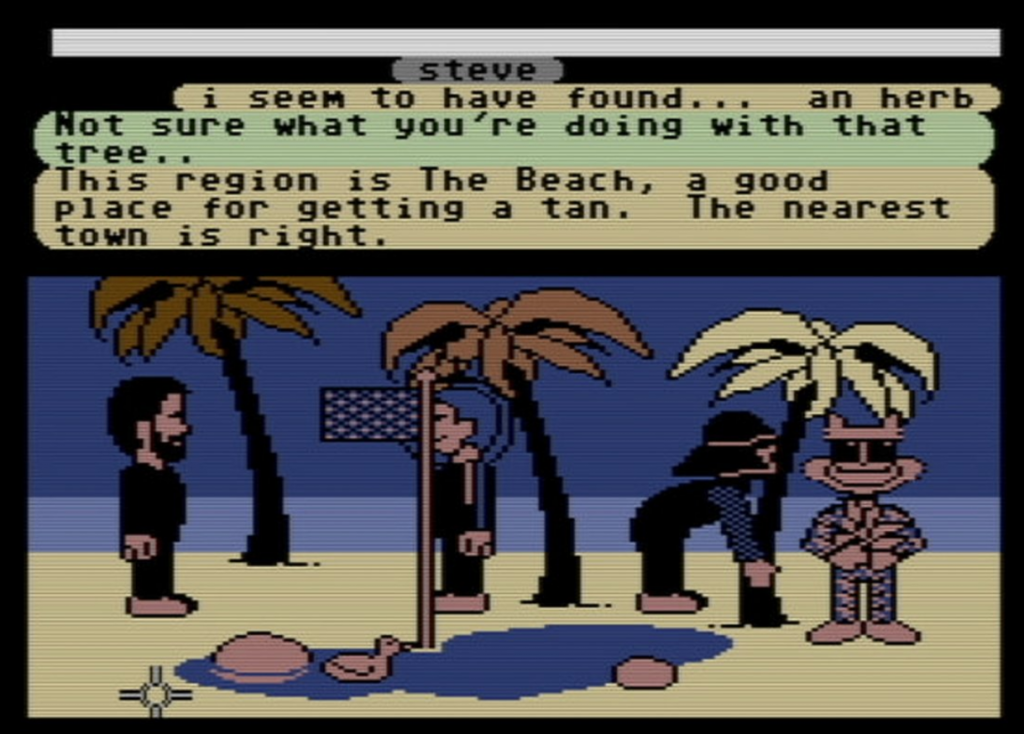

In 1984, a programmer named Chip Morningstar helmed a small team in Lucasfilm’s games division. After two years of experimentation, the team unveiled the fruits of their labor: a strange new personal computer game, the first of its kind. It was a graphics-based online experience called Habitat.

Available only on the Quantum Link dial-up network for Commodore 64, the unusual title operated for two years, from ‘86 to ‘88, never leaving beta. It was included with the Q-Link subscription service for the low price of $9.95 per month, plus six cents per minute to access “premium services.” Lucasfilm described Habitat as a virtual world where “thousands of avatars, each controlled by a different human, can converge to shape an imaginary society.”

While the history of custom character creators in video games is muddled and poorly documented, Habitat is the earliest example I could find of character creators as we know them. Yes, the ability to create a character had already existed in some text-based games, but Habitat had something completely new that makes its system familiar to a modern audience: graphics.

Starting with a doll-like blank slate, players could swap their heads out with a more appealing one from their collection, or spray paint their body another color. The options were limited, but they lit a spark. Suddenly, the imaginative aspect of pen and paper characters was fused with a clear visual representation: you could make it look like you. Sort of.

Habitat cut its losses two years later, relaunching as the pared-back Club Caribe and shredding its player base in the process. Lucasfilm Games soon became LucasArts, and shifted away from the online games market. Q-Link became America Online, the legendary firm who would soon provide the infrastructure for more well-known online worlds like Neverwinter Nights. And although Habitat’s rudimentary tools may seem quaint when placed alongside today’s intricate character creation systems, we can see within them the seed that would eventually blossom into games like Final Fantasy XIV, Black Desert Online, and Saints Row 2.

Many of the people I spoke to linked the online spaces pioneered by Habitat to the self-actualizing aspect of character creation. Ro Smith, a non-binary FFXIV player, relayed a similar experience.

“I had been roleplaying characters online in games and messaging services long before I knew I was trans or non-binary,” Smith said. Their formative experience as a female rogue in World of Warcraft, a game they discovered inside the stifling atmosphere of an all-male military school, provided an invaluable outlet to express a degree of femininity. They arrived at FFXIV as they explored their sexuality and, eventually, gender identity.

“There’s a normalcy to being gay in these spaces that’s overwhelmingly comforting,” Smith said. “Something about the fantasy setting and the way in which you interact with others makes your personal identity take a backseat, making it incredibly easy to be yourself, ironically.”

One fascinating chapter in the history of character customization revolves around the Saints Row franchise. Although it’s easy to mistake Saints Row for a hypermasculine Grand Theft Auto clone, the series has always been much smarter and more subversive than that. Saints Row 2 is often highlighted for the flexibility and maturity of its character creation options. While the game asks you to choose between male or female sex characteristics, virtually nothing else is limited by that choice.

“There is a slider that adjusts your character’s body type on a scale from ‘stereotypically masculine’ to ‘stereotypically feminine’, meaning there’s a lot of space to play in with regards to physical androgyny,” Niamh Williams explained.

She describes the character creator as “light years ahead of so many games I’ve played since.” It’s remarkably difficult to find a single word from the Saints Row 2 team said about the character creation system, but whether developer Volition realized they were providing an outlet for LGBT people to explore their gender or not, it’s all there in the final product.

Developer CD Projekt Red, known for their acclaimed series of games based on The Witcher, recently said that their new game Cyberpunk 2077’s character creator would have options in the same vein as Saints Row 2. In the words of Marthe Jonkers, a Senior Concept Artist on Cyberpunk: “You don’t choose, ‘I want to be a female or male character,’ you now choose a body type.” The team behind Cyberpunk wanted to let players define their character without being forced into binary gender options.

The usual suspects responded with sadly predictable fury. CDPR were clearly rabid leftists cramming identity politics into the entirely apolitical gaming sphere. The most stinging riposte to that argument was delivered by Mike Pondsmith, creator of the original Cyberpunk tabletop game, when he called Cyberpunk “inherently political” in a recent interview. While the irony of trying to detach politics from a genre revolving around the implications of unrestricted corporate governance may be lost on those crying foul on Cyberpunk 2077, eleven years on from Saints Row 2, the gulf between the reception of its gender-fluid character creator and Cyberpunk’s is troubling.

The controversy has the unmistakable whiff of manufactured outrage, where progress in the way character creators represent trans identities becomes just another proxy in the battle of the keyboard warriors’ crusade against “social justice.” But our space within the conversation around games is something the LGBT community has fought for and earned, and it won’t be relinquished without a fight.

Character creation has been wedded to self-expression from the beginning. In a fascinating Lucasfilm promotional video for Habitat, the narrator declares that a player crafting their character is “choosing a new look that will reflect his real self-image.” While that demonstrates the depth of thinking about character creation even at this early stage in its evolution, the reality is more complicated.

It is not only about reflecting the real self-image of players. It’s also about new formations of the existing image, with elements of self refracted and distorted, about the open exploration, creation, and dismissal of the self. The way we relate to the idea of the character mirrors the way we relate to our own identity, but it is a funhouse mirror, not a perfect reflection.

For myself, I can’t help but return back to my time with Ultima.

I was finally ready, after agonizing for an hour or two over her appearance. My perfect Ultima avatar. Sporting a badass gray ponytail and pink dress, she radiated magical power. And then my brother peeped into the room. I pointed at my new creation, beaming with pride.

“You’re playing as a girl? That’s gay.”

Or something like that. The exact words are difficult to draw into memory, but the laughter isn’t.

I don’t mean to cast him as the villain—these are the things brothers sometimes do. But there is certainly some part of me that died as I shuffled back to start over, whisking my Mage into the digital dustbin, replaced by that vanilla stalwart, the Warrior. He was fine too, I suppose.

But my Mage didn’t disappear entirely. Some part of her remained, tucked away in the back of my mind, connected inextricably to the experience of all those other queer people who would eventually find a home in other worlds. A place where they could create themselves, if only for a few hours.