Cyberpunk 2077 fails its queer players, but the genre is a whole other story

Representation and implementation of queerness in Cyberpunk 2077’s future was disappointing, to put it mildly.

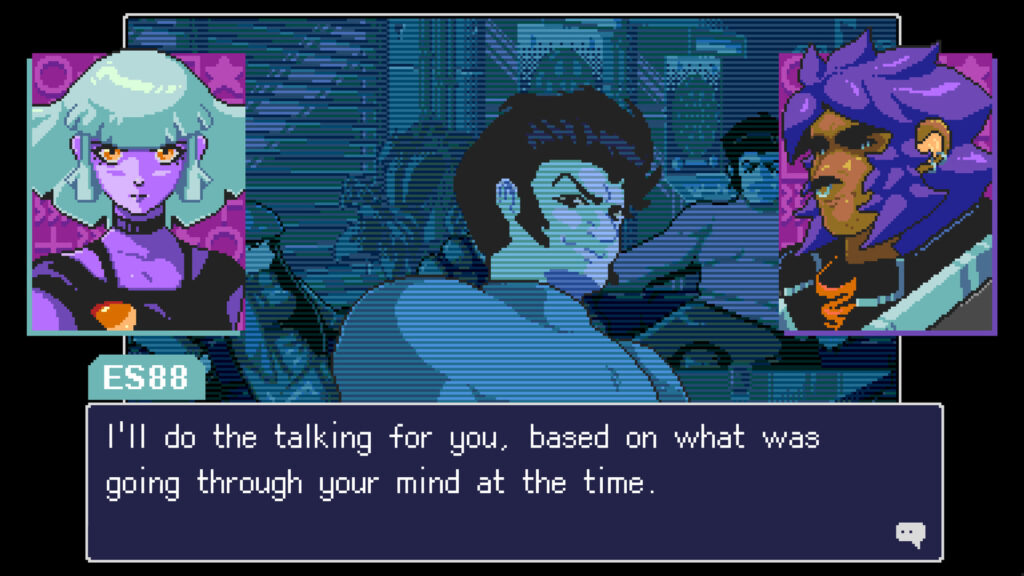

Nevertheless, queerness seems within arm’s reach in cyberpunk: we already have (or we are going to have very soon) queer cyberpunk video games like 2064: Read Only Memories, The Red Strings Club, Love Shore, and Hardcoded, and even the source material of the Cyberpunk tabletop role-playing game suggests a queer reading.

Keeping all of that in mind, I investigated a little further in order to understand why cyberpunk sometimes feels so resistant to queerness, how it could be queered, as well as how it’s already being queered. That is to say, how can we imagine non-normative cyberpunk narratives of sexuality and desire, and challenge existing narratives centered on a cisgender and heterosexual, and (often) Western, and white experience?

Cyberpunk fiction is strongly related to the concepts of post-humanism, the idea that humanity can be reconceived through technology and through our hybridization with it. As explained by N. Katherine Hayles in How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics, supporters of post-humanism think that our bodies are just hardware that can be replaced and customized without serious consequences to our software: the mind, that represents our true selves.

At the same time, post-humanism sees the whole reality as something that can be computed, and since it can be computed it can also be replicated by a machine. So to speak, the fact that computers can become “intelligent” implies that our brains are describable as computers. In William Gibson’s novel Neuromancer (that we can consider the archetypical cyberpunk novel, published in 1984) the body is either “a prison” or “data made flesh.” After the end of WW2 and during the Cold War, this vision brought together the first cyberpunk wave, the founders of cybernetics, and the US military complex (where the video game medium was born), with its attempts to computationally predict the weather and the trajectories of Russian rockets. Even nowadays, the real push for our advancements in cybernetics, robotics, and augmented/mixed reality often comes from the military.

That’s not queer at all: ignoring our bodies won’t make them disappear, but it will reinforce the existing privileges and hegemonies of those bodies that are considered “normal” and “neutral” (male, cisgender, abled…). In Cyborgs or Goddesses? Becoming Divine In a Cyberfeminist Age, Elaine Graham explains how nature and body have been first feminized and then, since they had been feminized and put in opposition to masculinized culture and rationality, they were rejected by a masculine culture (and cult) of technology.

Furthermore, unlike what techno-frat boys state, physical and real-world barriers are not actually dismantled in these cyber-utopias: cyberspace (the digital world of the internet, as seen as a world apart from ours) can ensure a level playing field, but you still have to own expensive devices and to have the necessary technological and linguistic skills in order to reach it. “In John Perry Barlow’s manifesto A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace cyberspace is for everyone, you can be everyone and do everything you want” Professor Edmond Y. Chang, author of Technoqueer: Re/Con/Figuring Posthuman Narratives, tells us during a video call. “But of course that’s not true. We think of cyberspace technology as a bottom-up technology, but in reality, it’s also very top-down: you take down the server and cyberspace disappears.”

In the introduction for 1986’s Mirrorshades anthology, a collection of what’s considered the canon of the first cyberpunk wave, Bruce Sterling tries to represent the movement as a revolutionary social critique linked to 60s counterculture, though he carefully avoids listing 70s feminist sci-fi writers among the forefathers/mothers of the genre. He erases the heritage of feminist sci-fi because cyberpunk novels would look quite less revolutionary when compared to works like Joanna Russ The Female Man, and the comparison would also show how much Sterling and his colleagues were actually ripping off (and depoliticising) characters and elements from 70s feminist writers.

Despite Sterling’s claims, the original cyberpunk is actually a quite conservative genre: Nicola Nixon notes that the protagonists of the first cyberpunk wave celebrate “the same initiative and ingenuity which has always characterized the American hero.” They are the future heirs of cowboys from Western fiction and of their next incarnation, the private eye of hard-boiled novels and noir movies. Cyberpunk protagonists dominate and penetrate a feminine and feminized technology, and they don’t fight against capitalism as a system but against Japanese conglomerates threatening US freedom of enterprise and technological innovation.

On the other hand, we can’t deny that cyberpunk does have queer potential. It’s probably not a coincidence that “gendered” and “marked by race” bodies as “defining elements of post-human identity” (as explained by Anne Balsamo) appear in Synners by Pat Cadigan, the only woman allowed into Bruce Sterling’s Mirrorshades anthology. Simultaneously, feminist writers were working on highly political takes on dystopian fiction (Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale was published in 1985), and we find many more feminist and queer writers in the second cyberpunk wave in the 90s and early 2000s, like Melissa Scott, author of Trouble and Her Friends. As Lisa Yaszek writes in her chapter of The Routledge Companion to Cyberpunk Culture, these writers “appropriate the classic cyberpunk image of the economically marginalized computer hacker to give voice to the experience of sexually marginalized groups, casting their hacker protagonists as both economic and sexual outlaws.”

It’s an uncommon representation in cyberpunk video games, even in the most LGBTQIA+ friendly ones: what we usually have is a somehow consoling and hopeful vision of a future where queerness is generally accepted instead. Technocrat Games and Wadjet Eye Games’ Technobabylon, one of the first commercial games to feature a playable trans protagonist (sorry, Tell Me Why), is an example of this trend, while Natalie the Knife’s tabletop role-playing game BLOOD & hormones, where we play a group of trans punks “in a cyberpunk future that wants them dead,” is an interesting exception, and it also highlights the relationship between queerness and the “punk” aspects of cyberpunk.

“For me, ‘punk’ is less of a genre axis and more of a political axis” Natalie writes me via email. “[T]here are many genres that end up being called ‘punk’ (cyberpunk, whalepunk, dieselpunk, etc), and the thing that ties them together in my mind is a focus on the experiences of the downtrodden. These genres imagine fantastical worlds full of magic and technology, but these worlds are full of people who suffer at the hands of the systems that control these worlds (corps in the case of cyberpunk; nobility in the case of a lot of whalepunk). If one approaches a ‘punk’ genre without addressing queerness, to me that means that they are failing to imagine one of the ways by which people are oppressed in our own world.”

But that’s only one of the ways cyberpunk is (and can be) queer(ed).

Cyberpunk can be queer because cyberspace can be queer – and queered. “In cyberspace, the transgendered body is the natural body” Allucquere Rosanne Stone writes in The War of Desire and Technology at the Close of the Mechanical Age. “The nets are spaces of transformation, identity factories in which bodies are meaning machines, and transgender – identity as performance, as a play, as wrench in the smooth gears of the social apparatus of vision – is the ground state.”

And cyberpunk can be queer because cyborgs can be queer – and queered. “I think what’s queer about cyborg bodies goes beyond the definition of queer as queer sexuality. Everything that unsettles norms can be defined as queer,” Professor Chang tells us. “The queerness comes when we really try to unsettle things and reimagine them and repurpose them. It’s difficult for games, because it’s an expensive media, and it’s an industry that’s trying to please a lot of people. But a cyborg body – or every kind of body that’s not the norm – can be defined as queer. We can say that the cyborg body critiques the idea (or queers the idea) of what a body is.” The concept of cyborgs also allows us to rethink our relationship with nature, since cyborg’s fusion between human and non-human problematizes our idea of human culture as something external to non-human nature.

“Cyberpunk as a genre owes a great deal to questions of ownership and validity of bodies” Natalie adds. “You buy an implant and your body is owned by a corporation; you jack into a virtual reality and you have taken on a new and different body entirely. These questions are deeply related to how trans people live in the day to day; our bodies are owned by the medical-industrial complex, which leases the things we need to survive (hormones, surgery, therapy) to us, and the desire to change your body or find a new one altogether is something that many trans people experience.”

During a video call, Heather Flowers, developer of Extreme Meatpunks Forever, tells us that meatpunk, their cyberpunk subgenre focused on technologies and giant mechas made of meat and flesh, tries to push this relationship further. “Various parts of meatpunk speak to the queer experience. People relate with the way everything feels uncomfortable and with the way everyone feels uncomfortable with their own body (because that’s not actually their body) in Extreme Meatpunks Forever. The mechs represent the idea of going from one flawed body to another differently flawed body, but also the idea of becoming monstrous. We are people who have been told for our entire life that we are monstrous for base aspects of ourselves, so to be able to embody that by entering into a monster and becoming that monster.”

Asking ourselves how a cyberpunk game can be queer goes to a much broader question: how can video games (in general) be queer? “The first step towards queer mechanics is questioning what’s actually necessary” Flowers claims during our interview. “Queer mechanics come down to subverting expectations, understanding exactly why things are the way they are so you can mess with them, and understanding the value in the lack of domination. Letting your characters lose, letting that loss have meaning, accepting and dealing with loss. Not just in a storytelling way, but in a way that actually progresses the mechanics forward.”

MidBoss’ John James, director for 2064: Read Only Memories, tells us something similar during another interview on Skype: “allowing players to experiment without the fear of failure is something that I feel is in, someway, queer”.

Extreme Meatpunks Forever and BLOOD & hormones are also games about a community, games where you do not have a unique protagonist and where characters must take care of each other. “I think part of the experience of making queer art and games about queerness is de-emphasizing [having only one] protagonist,” Flowers says.

So, a queer cyberpunk might be a cyberpunk focused on bodies, communities, and a lack of control, a cyberpunk that accepts both experimentation and failure. During our conversation, Professor Chang suggests that we might need something even more radical.

“The book I’m currently working on starts with a provocation” he teases. “Can you have a queer game when the basis of that game [the computer] is binary in nature? I think that video games can be queer, but maybe we are not asking the right questions or we are looking for the wrong solutions. We must ask not just how there can be queer people (or narratives) in it, but how the game itself, from platform up, can be queered. And I think that’s on some level, something (I don’t know what) must be queered about the machine, too. But if we take digital technologies as a tool and we put queer creators in positions of influence… that’d be at least a start. And we don’t only need queer creators, we also need to teach players how to think critically about queerness.”

In some way, when we ask ourselves how cyberpunk video games can be queer we are wondering how technology can be queer, and since computers have such a role in our life, we are wondering how our life can be queer. When we are in front of our computer, when we are tinkering with our smartphone, we are part of the circuit, we are part of the diffused and pervasive cognitive system of the internet. We are post-human cyborgs already.

It’s time to be queer post-human cyborgs.