My queer Hispanic heart beats for Miles Morales

In the spirit of Hispanic Heritage Month, I thought I’d explore a bit of my relationship with gaming through the lens of my Cuban heritage.

I had never really put much thought into the way gaming or my relationship to it could affect or be affected by Latin-influences. I grew up in Miami, where everyone around me was Cuban, so it never truly felt like I was a minority. It wasn’t until I moved to New York City later in my life where I began to consciously observe the massive influence my upbringing in my little Cuban pond had on the larger cultural ocean of NYC.

The contrast helped me appreciate representation in art and in the larger culture. That feeling when a little slice of your personal life is brought up on the big screen for the whole world to intake, feels like a window into your childhood home. In gaming, I never got the chance to feel the same feelings I felt when Pitbull was big on the charts.

However, when I sat down to consider this more, I could not for the life of me think of a single Latino character in gaming.

After blanking for a bit, I remembered that my experience with the indie title Read Only Memories: NEURODIVER (you can read my review here), was the most recent great encounter I had with a Latina protagonist.

Luna Vega de la Cruz was probably my favorite part of the game, and now I can see why. Her individual qualities as an upbeat quirky girl mixed with her use of Spanglish and those distinguishable Latin quips, resulted in a believable (and loveable) multi-dimensional character in a world of fiction. The subtlety of her Latin background was portrayed in brief moments of internal dialogue that mirrored a lot of the expressive thoughts I have myself that are distinctly Latino. Emotion, expression, and talking with your hands are some of the ways I see my own Cuban heritage show up in the way I walk about the world that I didn’t realize until I was in an environment where I stopped seeing so much of it.

Apply that thinking to gaming, and it’s no surprise to me that I didn’t realize how scarce well-done Latin representation was when I was so used to there not being any for so long.

Having a bit more time to sit, I remembered the few hours I had playing Spider-Man: Miles Morales. I was quickly reminded of how this new iteration of the iconic hero has popped off in the culture in recent years. Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse (and its sequel) were some of the best animated films I’ve watched in my entire life, and a lot of that was in due part to how Miles was written as a character.

I always felt drawn to the red and blue webslinger. He was in fact my hero of choice that, alongside Robin from the DC Comics, I believed to be a bisexual king. Spider-Man just oozes bi-vibes… and maybe I can’t explain it that well, but I think the simplest way I can is how Spider-Man’s story always involves the duality of his existence. Half superhero, half teenage boy. Bearing not just the responsibility of the world’s safety on his shoulders, but also the responsibility of being an active part in his family and home life.

It’s a story that I think subconsciously resonated with me, and as an adult, I see a lot of how Miles does something very unique for the Latinx community.

Looking into Miles’ story, I was trying to see the ways that his story differed from Peter’s and found that they’re actually not that different. He loses his father similarly to how Peter loses his uncle, which becomes a big catalyst for his growth and his relationship to his own responsibilities while managing grief. While they’re not that similar, the key differences much like the ones I observed in NEURODIVER, were in the subtitles, the perceived mundane day to day interactions or ways of thinking that Miles has.

Miles has an overprotective mother, very similar to my own. It’s a common sentiment amongst the Latin community how special the relationship is between a Hispanic mother and son. My own mother is loud, expressive, and is almost constantly worried about my wellbeing, even at 26. It’s stories like these that remind me how my experience with my mother is not unique to my own, and it’s something I find comfort in whenever I find myself struggling to be understood by her or when I try to get her to stop worrying about me. I am saving the world after all!

I also saw his perspective of having to step up to his responsibilities as the new “man of the house” after losing his father to hit very close to home. In Latin culture there tends to be this pattern that shows up in father and son dynamics that I’m sure most cultures can relate to that often airs on the side of toxic masculinity.

I’ve witnessed a lot of older men in my personal life that have had to take on more adult roles in their earlier life that ended up pushing a lot of their own needs to the side in order to look-out for those around them. A lot of this manifests as toxic-masculinity, where men develop the compulsion to look and act tough to mask the inner turmoil they haven’t given themselves the proper time to unpack.

I think the story of Miles handles this extremely well in that he’s always working to live for both himself and the entire world. This sees him fall on his face and disappoint others (which is to be expected with the pressure others put on him and the pressure he puts on himself) and it reminds me of how human that experience is.

The concept of living a double life, keeping up appearances to maintain a semblance of control over the world around you, is a story that many of us can relate too. It’s the reason why I see queer men struggle to come out in Latin families, because it challenges their perceived ability to be the masculine manly man of the house.

You hear a lot about sacrifice in Latin families, because there were a lot of them. The generational trauma in my life stems from the good will of the men who came before me, who were doing whatever they could to provide a good life for their family. A lot of that work included moving from Cuba to the States, working countless hours, and being away from home. It’s a similar story to Miles, who struggles to be home in time for dinner when he’s out saving the world.

It’s hard for family members to understand the weight on his shoulders when it’s not theirs to bear, and it’s something that reminds me to have compassion in my own life for the men who shoved their emotions down to help keep a roof over everyone’s head.

Miles’ depiction in the game made my heart warm when I would hear the dialogue between him and his mother, Rio. The little ways she would call him “mijo” reminds me of the times I’ve come home distraught from a rough day at school to vent to my mom about whatever was eating away at me. I think the game had a wonderful way of portraying the love that is often buried under all the conflict.

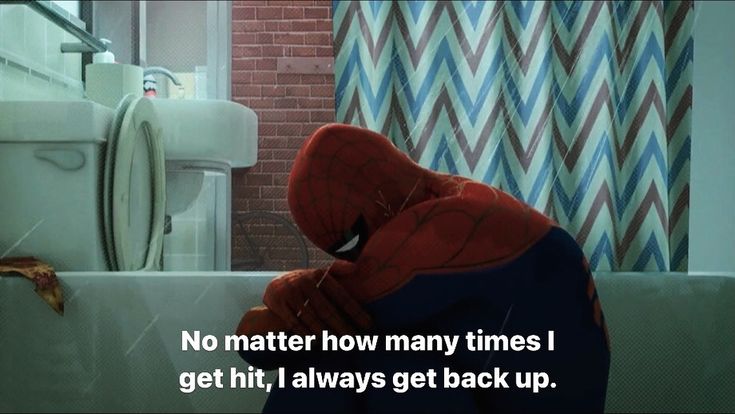

To close off my analysis of Miles, I’d like to emphasize a trait that he possesses that I believe the LGBTQ+ and Latinx communities can truly resonate with: resilience.

Time and time again Miles has to deal with loss and many tough battles that often mirror our own internal and external struggles that arise as a result of things outside of our control. The kinds of people we love, or where we’re from, are things that we can’t change that often set the scene for lifelong wars that we never wanted to fight and responsibilities we never wanted to take on, but have to in order to survive.

The way that all marginalized communities have had to endure generations of pain just to survive is something that can leave us feeling powerless, or it can be a testament to our power.

That no matter what life throws at us, we get up and we keep trying.

Because with great power comes great responsibility.