Comics Corner – The Historic Importance of ‘Gay Comix’, Part 5

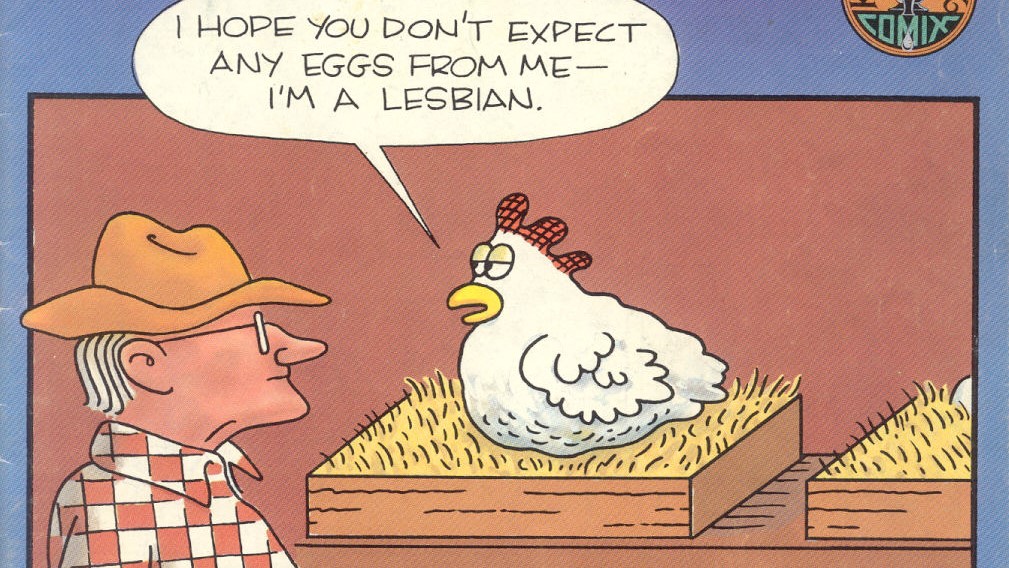

It is 1984, and things are changing for Gay Comix. While it remains arguably the most prominent publication for LGBTQ+ comics, behind the scenes, Robert Triptow has taken over as editor. Original editor Howard Cruse remains a key contributor, jointly headlining the front cover with Roberta Gregory, but the cover itself – a single panel gag by T.O. Sylvester – hints at what would be perhaps the anthology’s weakest instalment to date.

This is the latest in a series of retrospectives looking at the pivotal underground publication Gay Comix. You can find #1 here, #2 here, #3 here, and #4 here.

Maybe the problem was production tumult, with the handing over of editorial reins causing snarls in development of the issue, even though at this point Gay Comix was still an annual publication. Or possibly the mounting stress of being gay at a time when the AIDS crisis was mounting in the real world meant the various contributors to the issue weren’t exactly in the mood for creating the cheerier, comedic, or whimsical strips that had graced earlier issues.

Like the previous issue, Gay Comix #5 is almost weighed down by stories that either directly deal with the health crisis, or try to wrangle satire out of a confusing, scary time for the gay community. It’s not an element that’s present in every strip, but it’s enough of a factor to imprint itself on the issue as a whole.

Milo Paulsen kicks the issue off with the single page “Family Sundays”, a simple piece of near-nostalgia, with a couple of doting parents deciding the reason their son isn’t interested in dating girls is because he’s too busy with ‘wholesome’ activities such as sports. Of course, the son is gay, and harboring fantasies of other players. It’s a sweet little opener to the issue, a gentle flashback for readers who may remember when their own parents were oblivious to their sexuality.

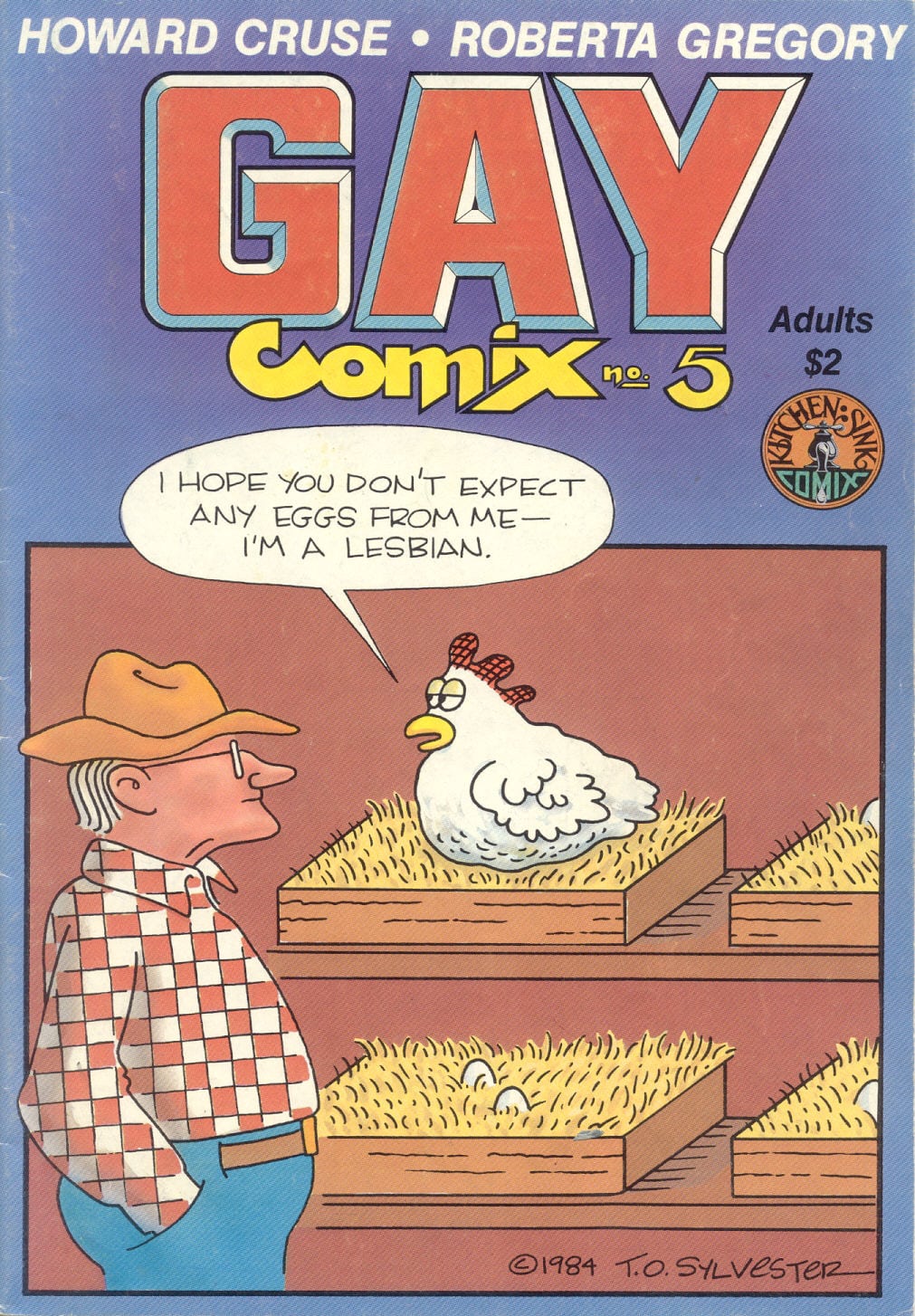

“It’s Attitude” by Michael J. Goldberg follows, the first entry in the issue to explore AIDS themes. To Goldberg’s credit, he tries to pastiche reality, using talking points surrounding the virus in reality – whether it was an epidemic or down to lifestyle, how rapidly it spreads, and how it was beginning to spread more noticeably among women – but instead warning of an entirely different threat: attitude. Unfortunately, it’s not entirely clear quite what Goldberg was lampooning by “attitude”, other than perhaps what we’d nowadays call “catty gays”. Goldberg’s characters are all exaggerated stereotypes for effect, and there’s no real end or point to the story other than a panel of a gravestone that, in hindsight, feels either remarkably raw or remarkably poor taste.

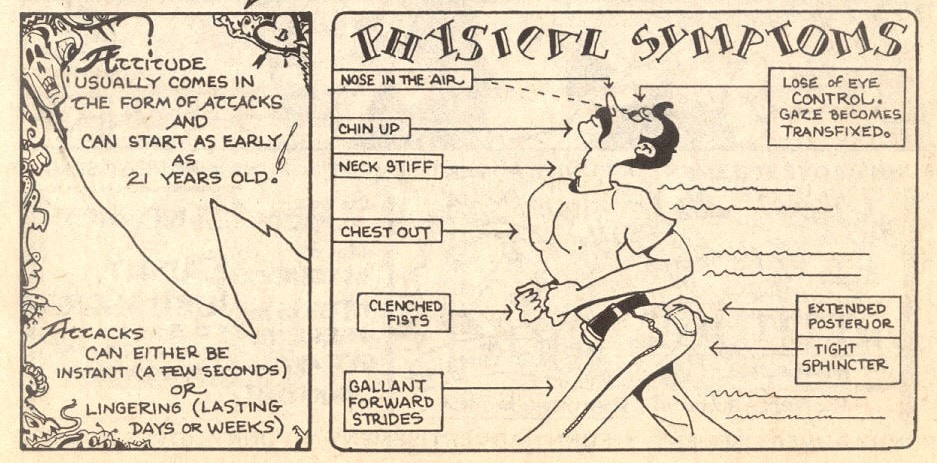

Tim Barela’s “Leonard & Larry: Revenge of the Yenta” follows, and is much stronger for returning to the tone of earlier issues of Gay Comix with a story focused on the foibles of queer relationships. Leonard’s interfering mother tries to set her son – and his “friend” Larry – up on a double date with her friend Ida’s daughter Lisa and her “friend” Linda. While readers will no doubt see the obvious twist, the run up allows Barela to explore how adult children can still struggle to come out to their parents, and how parents can ignore the evidence of their gay childrens’ lives.

If there’s a flaw to “Revenge of the Yenta”, it’s that it needs more space. Crammed into four pages, Barela’s beautiful, expressive artwork doesn’t have room to breathe, with panels overcrowded by speech balloons. Some of the jokes and reveals don’t really have space to land either – the same story over six pages would have been much stronger.

Roberta Gregory’s “Just Because” doesn’t directly address AIDS, but it does touch on how the gay community was increasingly being lambasted in the media. One half of a lesbian couple (who both go unnamed) is taken aback by the hatred spewed by a televangelist in the name of religion, but her partner tries to comfort her by pointing out that many religious people simply don’t know any openly gay people. She goes on to point out that “things could be a lot worse”, suggesting that “you could be lesbian and black and blind and poor…”, along with a litany of other woes.

Like her strip “The Unicorn Tapestry” in issue #4, Gregory’s work here is slightly confusing. To that point, “Just Because” almost reads like an argument for countering hate with compassionate understanding and for supporting intersectional minorities, but it swiftly follows with the couple’s car breaking down in a ‘bad’ neighbourhood, and having to ask a local resident to borrow their phone. When the person who offers them help turns out to be a black, blind, poor lesbian with a litany of other woes, the second half of the couple clams up and hides in the bathroom. It’s not clear what point Gregory is making – possibly that those who speak of inclusion aren’t immune to hypocrisy, or that the woman’s apparently intersectional talk was merely thinly veiled racism? – and not helped by the blind woman saying her situation means she’s “been given the unique opportunity to forgive 90% of the human race!” Possibly Gregory’s weakest contribution to Gay Comix to this point.

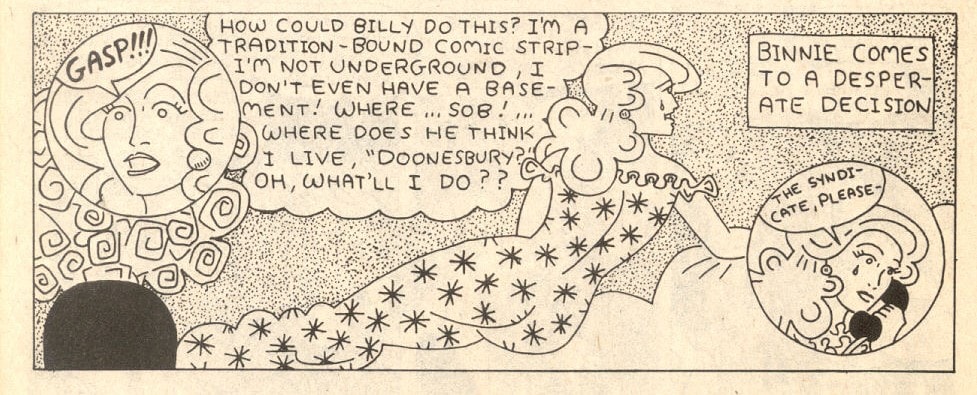

However, the next strip, “Binnie Blinkers” by Richard Valley is a joy from a comics history perspective. As Valley introduces with a text note, it’s a parody of the actual newspaper comic strip Winnie Winkle, which had run since 1920 (and would continue to be published until 1996). At the time of Gay Comix #5, the actual Winnie Winkle strip had just dodged a “gay scandal”, where the title character’s son Billy was going to have come out. This would have been a phenomenally groundbreaking moment – the strip was syndicated to well over 100 American newspapers, and was translated for international publication, so an out gay character appearing in it would have instantly been one of the most visible queer characters around.

However, several of those newspapers caught wind of the planned story direction and threatened to drop the comic if Billy was revealed as gay. This was despite an unspoken relationship with Billy’s “friend” Russ Miller – who Valley incorrectly refers to as Russ Manning, the name of the real life creator of sci-fi comic Magnus, Robot Fighter – having been built up for years. Alas, the outing was nixed, and Billy instead marries a never-before-seen older woman who already has children.

Valley flips the script, and has “Binnie”, his take on Winnie, aghast at being a “tradition bound” comic character yet having a gay son. She sells him out to ‘The Syndicate’, led by a thinly veiled parody of Daddy Warbucks from the Little Orphan Annie strip. In parody as in art as in life, this version of Billy also ends up marrying an older woman, but only because his version of Russ is kidnapped and held to ransom. Still, “the comic world is safe”, and heteronormativity reins supreme! It’s a brilliant bit of satire by Valley, and a history lesson, all in two pages.

Demian is another creator returning to this issue of Gay Comix, but his contribution is a radical departure in both tone and style from earlier works. “Zen and the Art of Bush Sex” abandons the almost ethereal approach of Demian’s previous comics – such as Gay Comix #3’s “The Tale of Cha-Lee and Sat-Yah” – in favour of something aping funny animal comics. Unfortunately, there’s not much to it – just a straightforward tale of a rabbit navigating a gay crusing area and struggling to hook up. While there’s some mild amusement in seeing anthropomorphic parodies of clichéd gay ‘tribes’ – a leather nun bunny preaching safe sex is a favourite – it’s not enough to salvage the strip. Visually, the artist’s intricate approach to backgrounds and environmental detail remains impressive but his cartoon animals are overly simplistic, feeling out of place in comparison. With no deeper or metaphorical layer to the work, the tale is the blandest of Demian’s contributions to the book to date.

‘Mesozoic Rescue’ by Michele Lloyd is similarly lacking any deeper interpretations, but it entertains simply by being brilliantly weird and borderline surreal. The strip features Lloyd’s creation ‘Spike, Punk Dyke’ – heavily tattooed, with a mohawk, spiked jewellery, and a shaven-headed girlfriend named Pookie – as she decides to create a time machine to travel back and save the dinosaurs from what really killed them: diarrhea. Instead, she finds that carnivorous and herbivorous dinosaurs were really wiping each other out in heavily armed shootouts, and decides not to save them after all, as “they’re no better than people!”

Spike does bring one egg back to the present with her as “hope for a new, peaceful race”, but the strip ends as it hatches, the infant dinosaur immediately pulling a gun on Spike and Pookie. ‘Mesozoic Rescue’ would be Lloyd’s only contribution to Gay Comix, and although there’s evidence of other ‘Spike, Punk Dyke’ strips floating around the internet, it’s unclear if the dino sticks around. A punk lesbian couple raising a gun toting dinosaur is peak relationship goals though, so that’s our head canon now.

In something of a reversal of Lloyd’s strip, “Better Times” by R. Campbell sees two male lovers, Evan and Geoff, transported from 1600s England to 1980s, when Geoff wishes they could live in a world where their love was accepted. Unfortunately, they materialise in a sex party, and discover the modern world may be too accepting for their tastes.

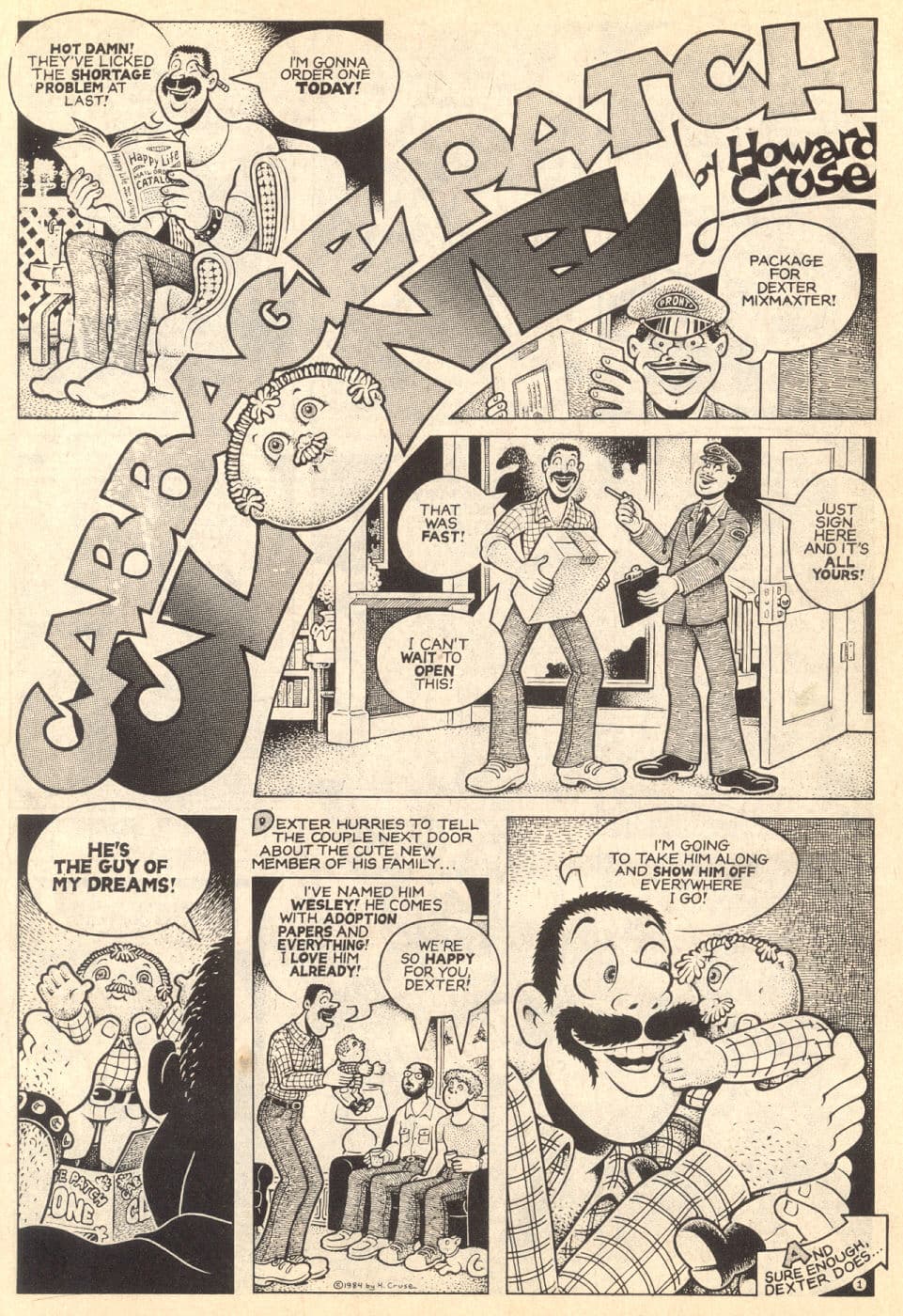

Howard Cruse’s entry this time is “Cabbage Patch Clone”, which ingeniously takes the (real, yet bizarre) Cabbage Patch Kids riots and uses them as a basis for a story that explores the tendency for some gay men to want to date basically themselves (hence ‘clone’). Our not-exactly-a-hero, Dexter, orders a Cabbage Patch Clone, names it Wesley, and treats it as a new boyfriend. Between Dexter introducing Wesley to his friends and neighbours, taking him on holiday, and fulfilling certain physical desires, it’s clear Cruse is also lampooning men who want pets, not boyfriends, a point made all the more clear when Wesley comes to life.

Calling out Dexter for his narcissism and clinginess, Wesley goes on to critique everything from basic values to housekeeping and even differences in sexual tastes. Dexter, in turn, shows precisely zero personal growth, throws Wesley into the trash, and orders a new Cabbage Patch Clone – because “maybe if I order another one, it’ll all work out better!”

Cruse’s art is as brilliant as ever, his trademark detailed line work, heavy inks, and stunning dotwork shading making the strip a treat for the eyes. It’s his willingness to call time on gay men’s poor behaviour with impeccable comedic delivery that elevates his work though, holding a mirror up to the reader whether they want to see the reflection or not.

New editor Triptow contributes the five-page strip “When Worlds Collide”, where an ageing drag queen runs into trouble on stage when their dated, sexist jokes offend an audience mostly comprised of lesbians. It’s supposedly based on real events, which we can believe – for better or worse, it remains a relatively timeless piece, as lesbians are often still the butt of lazier drag queens’ jokes.

Still, Triptow’s art here really impresses, capturing the “female impersonation” of the drag queen in a way that really presents the blurred gender roles, while also creating a fantastic sense of space for the theatre it’s all taking place in. It’s a real evolution for Triptow’s skills from his earlier, newspaper style “Castroid” strips.

The final ‘main’ strip this issue is “Hot Night Out” by Jennifer Camper, published mononymously as just ‘Camper’. It’s a short one at three pages, with a simple premise – a lesbian couple go to a women’s bar to try to pick up “new friends”. Instead, they’re disappointed by a host of rejections, judgemental types, and women passed out on quaaludes (it was the ‘80s), before realising they were better off staying home and, err, entertaining themselves. Camper’s artwork is breezy and energetic, but the pages are really brought to life with some dynamic panel layouts that burst the ‘frame’ of the page, while the final shot may be the most brazen and joyous presentation of lesbianism in the series to date.

The issue is rounded out by a handful of one-pagers that again centre on the confusion and paranoia surrounding AIDS. Jerry Mills’ “Poppers” strip returns, with promiscuous jock Billy finding promiscuity difficult when even gays at bath houses are scared to have sex, while two separate instalments of Vaughn’s “Watch Out!” both deal with fear of the virus. In the second of the two, AIDS is imagined as a literal monster, hunting gay men wherever they go, and leading one character to remark that “whatever the cause (of AIDS), we have to live with the effect.” It is not exactly a laugh riot.

As ever, looking back on on any issue of Gay Comix from more than 30 years later, it remains an important insight into the attitudes and concerns of the time. However, this fifth issue of feels the most slapdash to date, an anthology that both lacks a common theme but is also overshadowed by the one thing no queer person could avoid thinking about in 1984. While not totally lacking in quality, this is the closest the series has come to coasting. Thankfully, better things are to come in its future.