Having a gay old time: the significance of older queer men through video games

There’s always been the question of ‘where are the gay men in video games?’ and often the answer is confused silence. But looking back throughout video game history, we get to see the portrayal of gay and queer-coded men back then, and the cultural significance they’ve brought to the present.

Video games are a young medium, despite being as old as some of our grandpas. It all began in the 1960s, with the advent of gamer grandpa Ralph Baer’s Brown Box, a prototype console he built while working for defence contractor Sanders Associates. In 1972 he licensed a version of the Brown Box for commercial sale: the Magnavox Odyssey, widely credited as the first gaming console ever created. 2022 is exactly 50 years out from that historical moment.

Within these 50 years of games, LGBT characters only began to emerge in the 80s, when games had awakened to the possibility of telling complex stories. In the golden days of the Apple II, Amiga, and Commodore 64, text adventures became the first real platform for storytelling in games—sadly, most early LGBTQ+ representation in these narratives came in the form of villains, or more often, side characters meant to be the punchline of bad jokes. Though there’s no need to linger there; let’s fast-forward to the early 90s, in the time of bizarre live-action cutscenes and clunky point and click inventories.

The first gay character to have a speaking role in a computer game was a thirty-something bookstore owner named Alfred Horner from Dracula Unleashed, a 1993 title for the SEGA CD. Despite the system’s shortcomings and often mind-boggling catalogue of titles, Alfred’s presence as a speaking character was a significant milestone for LGBT characters in gaming. Since his appearance, we have played as and fought for so many more.

From the flashbang novelty of the arcade to the home console and PC, games were only just beginning to develop the emotional maturity to portray complex, older characters. And in all fairness, so were we — audiences love youth. We crush on handsome, able-bodied twenty-somethings in a world where sex appeal is currency. The same is true for LGBTQ+ audiences; we are, understandably, tired of being denied what straight people have enjoyed for centuries. It’s only fair that we get our fair-eyed Romeos and jacked up He-Men, too.

But where do the rest of us average, garden-variety gays go? What about the lesser hunks pushing fifty at the gym? The underpaid professors with greying hair? The full-bearded, beer-belly powerhouses haunting pubs after hours? How do we make room for aged, grandpa bods that many might not read as sexy? They may not measure up to a given aesthetic ideal, but more often than not, these characters have a wealth of experience to share about life, love, and the pursuit of flabbiness. Those who can appreciate big, cuddly quinquagenarians know the truth — we could stand to learn from their humble dorkiness, ourselves. Nothing says “true love and acceptance” like dinky old men in love.

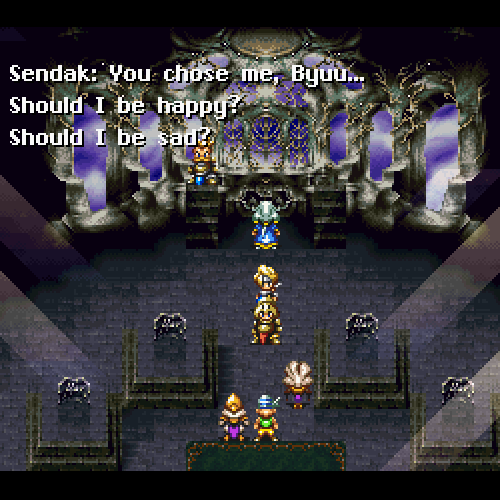

Squaresoft’s 1996 title Bahamut Lagoon introduces us to a greying summoner named Sendak. The game features two optional romances, both played primarily for laughs, and Sendak is surprisingly one of them. Having the option to choose a gay old man over a princess was a bold and revolutionary choice at the time, comedic or not. Byuu, the game’s protagonist, can accept Sendak’s advances, and in so doing earn unique interactions and dialogue. The wizened magic user with a tall staff is a familiar trope in the RPG genre; he evokes familiarity and cosiness alongside the novelty of using this well-trodden character trope in a gay romance. It’s like getting up close and personal with gay Gandalf, or Merlin.

Sendak’s name is also shared by gay children’s book author Maurice Sendak, though likely by coincidence — Maurice Sendak was not openly gay until 1996, the same year Bahamut Lagoon was released. A wholesome coincidence, but nevertheless: a resonating echo of elderly gay joy – both real and fictional.

With the exception of Sendak in Bahamut Lagoon, most examples of elderly gay men are contemporary, with one instance as recent as 2021 — Helmut Fullbear and Bob Zanotto from Psychonauts 2. Who doesn’t love a bookish nerd and a viking-styled rock star holding hands?

In a wacky universe of body-swapping brains and monarchist psyops, Bob and Helmut’s enduring relationship is something of a miracle. After a vicious defeat in The Battle of Grulovia, Helmut is presumed dead for many years. Bob, in his absence, suffers a deluge of alcoholism, depression, and abandonment issues. Helmut (living as an unlabeled brain in a jar) faces his own sensory struggles as a result of being disconnected from his body for so long. Both are ultimately reunited, survive the game’s events, and remain adorably in love. Most poignantly, they are allowed to be physically and emotionally affectionate with each other on multiple onscreen occasions. It is one of the most sincere gay romances in all of gaming history, punctuated by held hands, hugs, and coy remarks about the ethics of smooching “with borrowed lips”.

More than that, Bob and Helmut’s experiences have made them stronger and both are instrumental in resolving the game’s overarching story. While the golden days of the Psychic Six have long since passed, the two live up to and even surpass the legends they once were. Together they build a new, living mythos in the world of Psychonauts.

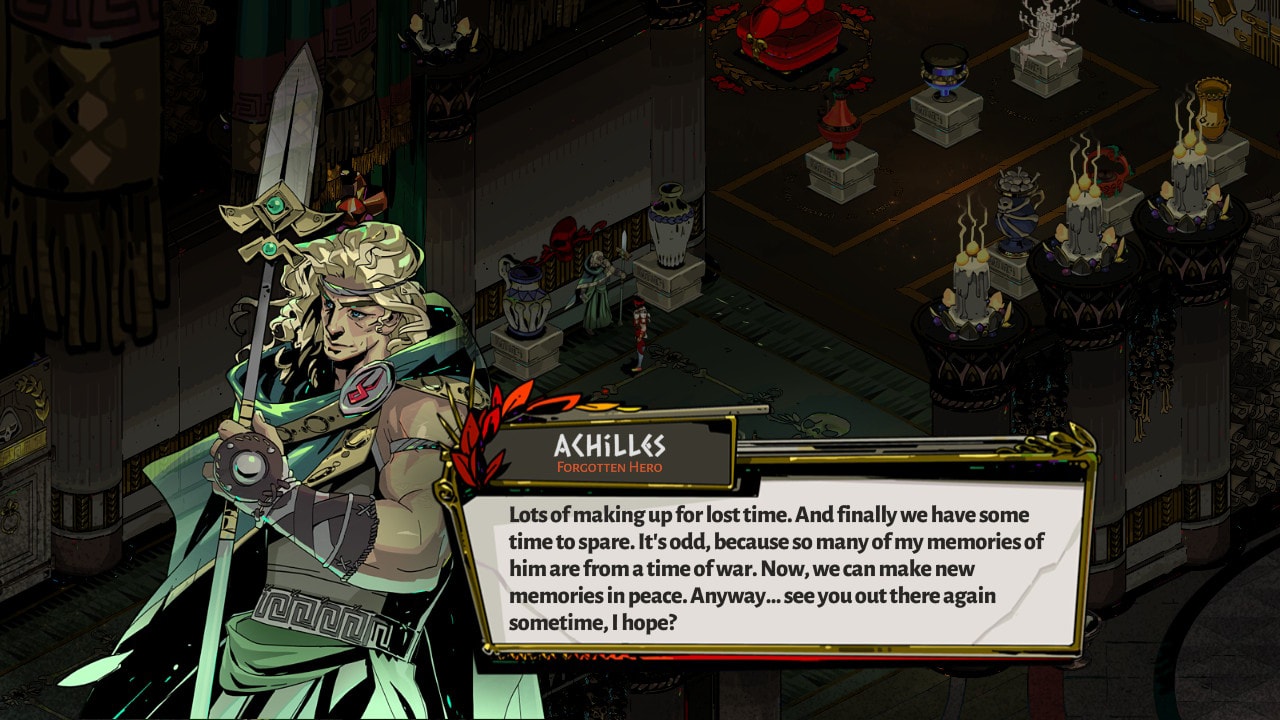

Scholars and historians have been arguing about the relationship between Trojan War heroes Patroclus and Achilles since time immemorial. At long last, Supergiant Games has an answer for them — contemporary classics come to life in their 2018 roguelike, Hades. The game allows players to help reunite wayward lovers Patroclus and Achilles in a rich and extensive sidequest. Supergiant’s version of Achilles is something of a martyr. He signed an agreement with Hades himself to train his son, Zagreus, in exchange for Patroclus’ stay in Elysium (the most pleasant layer of the Underworld by far). This agreement binds him to the House of Hades, where he cannot leave to visit Patroclus. He believes he did what was best, sparing his partner from another lifetime’s worth of suffering in Tartarus; his loneliness is a small price to pay for Patroclus’ relative comfort and safety.

Similar to Bob and Helmut, Patroclus and Achilles share a heartfelt reunion after incredible hardship. The aftermath of war and fine-printed contracts is kind to no one — estranged from one another in death, they must overcome feelings of guilt and despondence to mend their broken hearts. With age comes wisdom, and from wisdom comes strength; their reunion is a testament not only to their strong wills, but also to the very concept of a love tempered but enduring.

Nostalgia is just as persistent as love, and nobody does gay nostalgia quite like ZA/UM’s 2019 CRPG Disco Elysium. The game is a postmodern masterpiece defined by everything it is not about; the bygone days of disco and revolution inform the lives of its characters as they navigate the “after”.

The game’s deuteragonist (and arguably most beloved character), Kim Kitsuragi, tells us flat-out that he is gay. By the time the player encounters the above conversation, they will have already been exploring for hours. The game cleverly endears the player to Kim well before this reveal, cementing his status as an integral part of the story, in spite of diegetic and real-life homophobia. More than that, this same conversation also pertains to the main character, Harry, exploring his own identity — one would be hard-pressed to name a single title other than Disco Elysium where a 44-year-old protagonist gradually comes to terms with his bisexuality (while solving a murder case, no less).

Coming out is a familiar yet underrepresented story in games; many people live their entire lives in denial of their sexuality. Others only find out after they have been married for years. Harry would not be the first confused and heartbroken divorcee to make this journey. What’s more, players learn through Harry that even from the bottom of the bottle, there is no such thing as “too late”. For gay audiences, whether old or young, that hope could mean the difference between life and death.

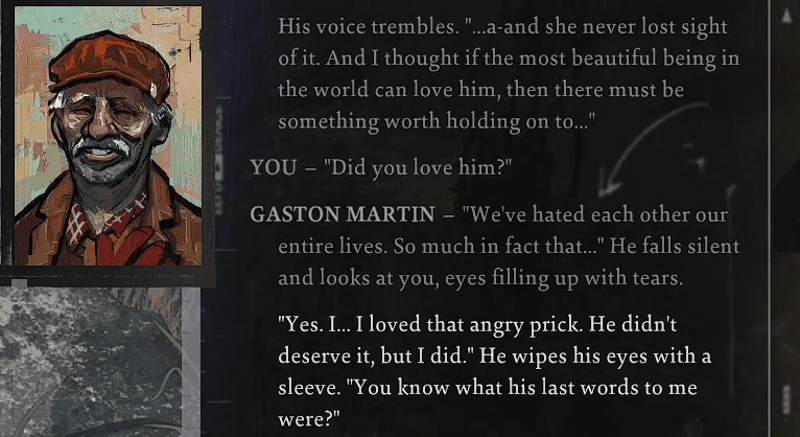

More tragic are two elderly characters named Gaston and René. The pair have been friends for 79 years, but are never able to act upon their buried love for each other. Two melancholy conversations with these characters allude to internalised homophobia and feelings of regret between them, including a direct confession from Gaston after René has passed away.

Though the two are often shown arguing about their personal politics, they always had a constant companion in one another. Together they outlasted a continental transition from a monarchy to a commune, to a Zone of Control. Against the odds of war and international suppression, they endured, and while they no longer have the chance to make their confessions, it was arguably never necessary to the longevity of their mutual feelings. Surviving history hand-in-hand is, in itself, an act of love.

Human beings develop emotional maturity through experience. Facing and enduring hardship teaches us the value of happier days, and tempers us for trials ahead; the same is true of games, both diegetically and in reality. As we continue to build upon the young foundation of game history, the medium grows alongside us. The electric array of chips that comprised the Amiga’s silicon brain could only dream of its descendants and their accomplishments. In the wooden accent panels and white-plastic shine of the Magnavox Odyssey, we found a spark to guide our way forward.

From tasteless villains and stereotypes to wizards, psychics, warriors, and socialists, gay men in games have come a long way. Their wisdom is our wisdom; in 2022, we are able to represent all facets of the gay experience, and the cultural impact of gay love pulling through come hell or high water.

There is strength in antiquity and — no matter how weathered or forgotten — our elders always have a few stories to tell.