Here’s how Blaseball queers narrative control – and why it’s important

Imagine sports, but queer.

What does that look like? Obviously we get rid of real-world problems, like the homophobia that stops athletes coming out and transphobic discussion of who plays in which leagues. But what do we change? Maybe we get rid of gender-split teams entirely. Maybe we stop holding onto ideas about how human athletes should look or behave. Maybe we get rid of the need to be human entirely. If any of that sounds a little bit interesting, you might like Blaseball. It’s the — the internet’s favourite ‘splort’, where nothing — gender, physics, gods — gets in the way of a good ball game, and fans decide what happens next. It’s here, it’s queer as in LGBTQ, and queer as in weird.

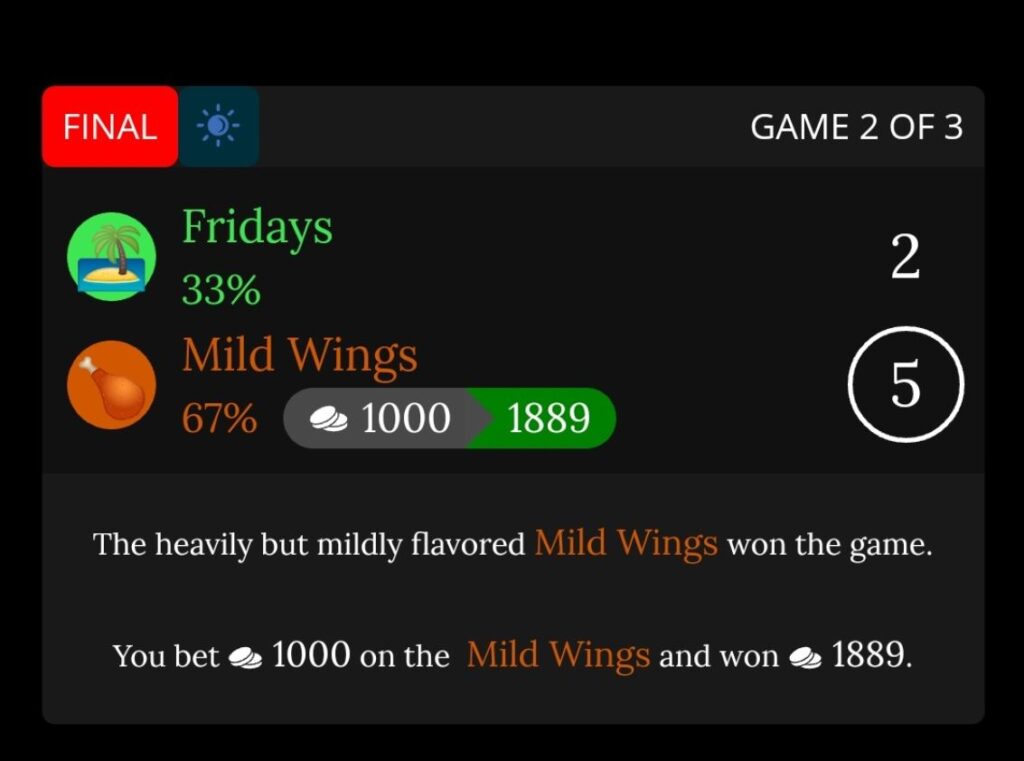

Blaseball is, at its core, a browser game where you bet on hourly games of fantasy baseball. Betting on winning teams gives you more in-game money that you can use to place more bets that season. Each season lasts a real-world week: games are Monday to Friday, the eight-team post-season to decide the series champ is Saturdays, and Sundays are for rest. There’s also an election every week where fans spend currency voting for decrees (changes to how Blaseball is played) or blessings (improvements that are granted to a random team). These fan-voted changes are where much of the weirdness comes from.

At the end of Blaseball’s sixth season fans collectively did some necromancy. Back in Blaseball’s first season, fans voted to open the Forbidden Book. Since then, rogue umpires have wandered Blaseball’s pitches, occasionally incinerating players. Jaylen Hotdogfingers, pitcher for the Seattle Garages, was the first to be obliterated. Come Season 6, fans realized that a new mechanic, designed to move a popular player between two teams, could actually be used to resurrect players. So fans rallied to bring Jaylen home to the Garages. It worked — but Jaylen came back different. Suddenly the batters she was bowling against found themselves likely to be incinerated, just as she had all those seasons ago. And that’s before a squid-esque god, known as the Monitor, showed up demanding tribute…

Blaseball’s gods — so far, a peanut, a squid, and an ancient coin — have simple images, but the splortspeople don’t have any physical representations. The fandom creates lore for its players, based on little more than ideas. Beasley Gloom and Workman Gloom, originally a pitcher and a batter respectively for the Charleston Shoe Thieves, are a dog and his owner. The Hades Tigers’ Mummy Melcon is a bandage-wrapped tea-brewing Egyptian corpse. Eugenia Garbage, a Canada Moist Talkers batter, is a sentient pile of junk. But there’s nothing that binds you to this fanon. My partner thinks of Eugenia Garbage as a pink-haired trans femme who proudly self-identifies as trash and loves ironic tattoos. Is renowned batter Jessica Telephone a regular human-ish woman, or a hellish demon, or a telephone-faced body-horror amalgamation? It’s up to you!

This lack of canonical physical traits means Blaseball players can be whoever you imagine — whatever age, race, gender, orientation or species you want, playing together in one equal-opportunity league. Queer people have long been drawn to shape-shifters, dreaming of the ability to transform between different versions of ourselves to best reflect our feelings; what’s queerer than a character who looks physically different depending on who’s imagining them?

While the Blaseball fan-wiki catalogues agreed-upon fanon, itthey recognizes the multiple interpretations through the “Interdimensional Rumor Mill”; whenever you look up a player, the player lore is loaded randomly from all the options fans have submitted. This adds to the queer rejection of absolutes: nothing is set in stone. All the players are in flux, with all their backstories existing simultaneously. This lack of canon and agreed vagueness means that queer people can insert themselves into fan cultures like sport – where they are traditionally excluded.

Blaseball has canonical developers, of course — the Game Band. But they’re not totally in control of the story: they respond to the whims of fans. When fans decided to resurrect Jaylen, the devs saw these conversations happening over Twitter and Discord and had to plan how to respond to this limit-pushing. The Game Band are like a long-suffering Dungeons and Dragons DM, while the fanbase is an entire party of wise-cracking wizards who keep looking for bizarre loopholes in the rules. The DM, while technically in control of the story, keeps having to adjust to whatever wacky scheme their players come up with next and look for ways to integrate fan plans into the game.

But Blaseball’s fan community is not a monolith. There are factions who are aggressively anti-fan lore, fan artists who get popular creating their own versions of players, and various different fake publications might use different pronouns to refer to the same players. How fans interpret that is up to them.

On a meta level, fans of Blaseball are essentially roleplaying as sports fans already, by talking about this fictional splort as though it were real. Some fans go even further and roleplay as players or whole teams on Twitter.

When the Mexico City Wild Wings’ Twitter account complained that the team was in the Mild league, the official Blaseball Commissioner responded — and kept responding — as it escalated into a (fake) legal case complete with (fake) legal documents. When Jaylen Hotdogfingers was loophole-abused back to life, the Commissioner claimed to be as confused as anyone else. When the Unlimited Tacos persuaded fans to work together to immobilize the entire team’s pitchers (why? To see what would happen if a team had no pitchers) the devs responded with Pitching Machine, a mid-range mechanical marvel that slowly developed a taste for human blood.

So the team behind blaseball are eager to have queer shenanigans in their game. They’re also committed to destroying oppressive systems in real life. An early season blessing, Eat the Rich, is emblematic of their beliefs. They supported progressive Los Angeles city council candidate Nithya Raman with Blaseball-themed artwork — and celebrated her historic win on their Twitter feed.

Blaseball shows us you don’t need characters or even graphics to make a game queer. All you need is an idea and a story that people can latch onto, and a development team who embrace that. By centring fan culture, Blaseball shifts the game from a product fans consume into a shared story that everyone helps create together. It’s a weird utopian cosmic horror crowd-controlled splorts saga — and what could be queerer than that?