Comics Corner – Wandering Son is a touching reminder that trans kids exist

Manga and anime don’t have terribly good reputations for how they represent sex, sexuality, or LGBTQ+ people. Both forms of media are rife with fanservice, often targeted at straight male audiences, and attempts at portraying queer characters are typically either painful stereotypes or fall into the yaoi (male-male character pairings, with stories targeted at straight female readers) or yuri (female-female, also generally aimed at women, although not necessarily gay women) genres. Yet despite the mountain of cheap titilation and clichéd gay characters that western fans may most commonly be exposed to, Japanese creators are no less capable of producing revolutionary and transformative works that deal with queer issues in sensitive and heartfelt ways.

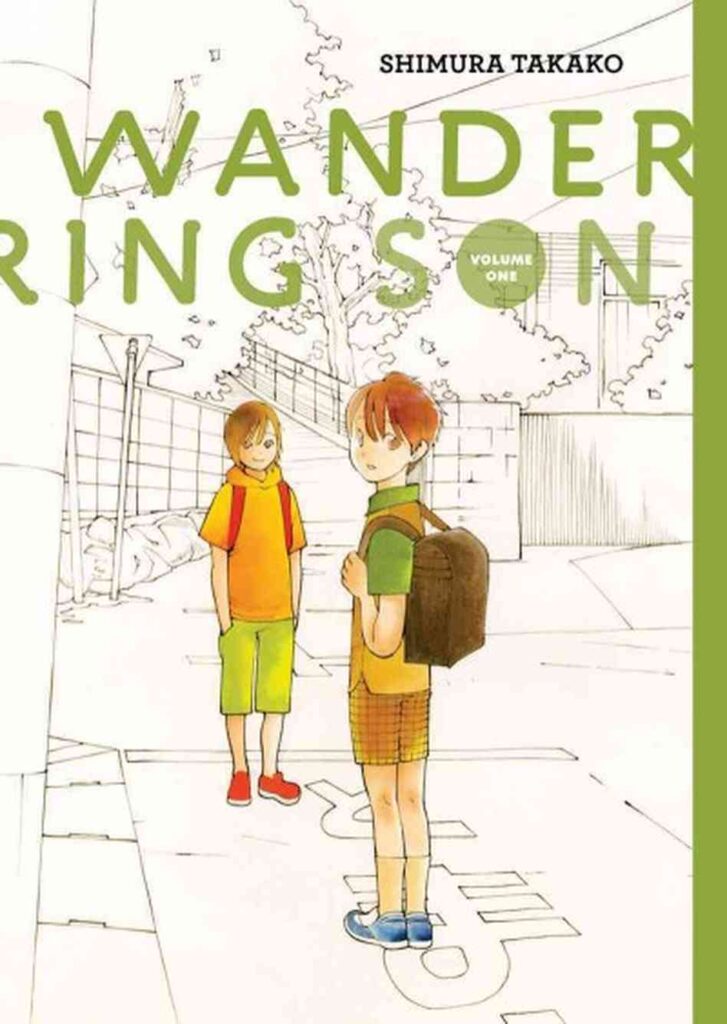

One such work is the sublime Wandering Son, by Takako Shimura. First published in 2002 in Japanese anthology Comic Beam, the series follows 11-year old junior high school student Shuichi Nitori and his friend Yoshino Takatsuki over the course of several years, growing and adapting to the world around them as they approach adulthood. It’s not just coming of age story though – Shuichi is a boy who wants to be a girl, and Yoshino is a girl who wants to be a boy, and the series follows their journey without exploitation, sexualisation, or cheap laughs.

Shimura deftly explores the burgeoning identities of her heroes with tenderness and grace, showing that trans kids know their gender from an early age, even if they don’t necessarily have the language, framework, or role models to understand or describe their identities immediately. Shuichi is shown to like dressing in feminine clothes and prefers gentle indoor activities to the sports male friends enjoy, while Yoshino rejects femininity in a way that goes beyond being merely a “tomboy”, hating female clothes and opting for a “boy’s” haircut. Early on, the pair bond over their similar experiences, finding a sense of solace in each other, but soon their circle is expanded with friends who support and encourage them in exploring their gender identities.

Saori Chiba is one of the first and most important allies the pair make at school, a classmate who takes an instant liking to Shuichi in particular. Away from class, she pushes Shuichi out of his shell, giving him the confidence to dress and act as femininely as they like, even gifting him a dress. Later, the young pair meet Yuki, an older trans woman, and her boyfriend Shiina, who becomes something of a mentor to the two.

As the series progresses, Shimura uses the ageing of her characters and their onset of puberty – with bodily changes such as Shuichi’s voice changing, or growing more hair – to explore gender dysphoria. Before this, Shuichi’s gentle features and slight build helped to “pass” as a girl, but the deepening voice in particular starts to cause real concerns. Similarly, Yoshino is regularly given unwelcome reminders of being assigned female at birth, with male classmates teasing or awkwardly flirting.

What really makes the series stand out though is that it is neither a simplistic introduction to trans issues, nor a heavy-handed treatise on the trials faced by trans people (although it certainly doesn’t shy away from that either – Yuki in particular has a sadness to her, and as readers learn more about her past, it’s hard not to share in that pain). Instead, it’s a heartfelt slice-of-life, told calmly and almost quietly, with the humanity of its characters first and foremost throughout.

Like Gengoroh Tagame’s My Brother’s Husband, Wandering Son illuminates an LGBTQ+ issue that is delicate for the domestic Japanese audience. Unlike Tagame’s work though, Shimura’s focus on trans identities in general, and trans children in particular, makes it powerfully relevant for western readers too, especially as trans people’s lives and rights are increasingly politicised in real life.

Wandering Son was translated into English by US publisher Fantagraphics, although at time of writing the first four volumes are out of print, and publication seems to have stalled at volume eight (of 15 Japanese volumes). Still, the series is more than worth tracking down, as Shimura’s tale ultimately proves one of the best explorations of trans identities to be found in manga. It’s not the first time Shimura has touched on LGBTQ+ issues in her manga though – the creator frequently explores queer issues in her stories, with a particular focus on lesbian pairings. Aoi Hana, or Sweet Blue Flowers, is perhaps Shimura’s best known work aside from Wandering Son, and all four volumes are translated and available in English, for anyone interested in Shimura’s work without having to pay premiums on the second hand market.

Alternatively, Wandering Son received an anime adaptation in 2011, directed by Ei Aoki. The series is a beautifully animated take on the series, and although it doesn’t cover the full events of the manga, all 11 episodes can be streamed on Crunchyroll. Whichever way you approach the series though, the warmth and empathy of Shimura’s work shines through, making Wandering Son an absolute must.