Personal Histories & Political Violence: How queer-run Sealbee Games used grief and protest to develop Bean Sidhe

Bean Sidhe: A Story of Family, Death and Resistance is a personal game about life, death and resistance from the independent, queer-run Sealbee games.

Led by Emily O’Neil (she/they), I was lucky enough to sit down with them for a talk on the game, the various inspirations behind it and the power of using personal histories to understand contemporary political struggles.

Sealbee Games began as a personal project for O’Neil, offering an outlet to learn and experiment with game development while they were working their day job as a data analyst. However, never one to be bored, O’Neil gradually began to move beyond this, reaching out through their network to form a team of like-minded, almost exclusively queer, game developers and actors.

Emphasising community support, the studio has adopted a transparent financial structure with the primary goal of raising funds for queer individuals and communities in need, a shared goal among the team that has helped develop a strong sense of purpose and solidarity among them.

These core tenets of queer advocacy and justice within the studio serve as the backbone to its development ethos, ultimately leading to the creation Sealbee Game’s Bean Sidhe. However, as O’Neil describes, the initial inspiration for the game came in three specific waves.

First, alongside meeting their partner Kris in 2013, O’Neil began participating in the BLM protests, feeling the call to do so after having witnessed a number of friends affected by racialised violence. Talking about the impact this had on them at the time, O’Neil explains: “I was trying to find, like, anything to grasp onto that … helped me kind of cope with the fact that I’m seeming my friends get rubber bullets aimed at them in the streets and, you know … friends of mine would literally walk into alleys and not return because they would get black-bagged by cops and thrown in prison.”

Second, in 2019 O’Neill experienced the first of what would eventually become a number of deaths, forcing them into a state of grief and reflection. The combination of these life-altering events culminated in a feeling of uncertainty, a desire to engage with the various traumas they had experienced but not exactly sure how to go about doing so.

Then, at a friend’s suggestion, O’Neil decided to look back at their Irish ancestry in an effort to both understand their family’s history and the impact of colonial violence in a context they could relate to more directly. With this in mind, they gradually began to dig into various aspects of Irish culture such as music, folklore, language and history, focussing in on the country’s republican movement and how it related to contemporary American politics.

As O’Neil describes, these ideas percolated for a while but nothing became of them until 2024 when the realities of Trump’s second presidential term offered the final stroke of inspiration. Staring down the barrel of Project 2025, O’Neil felt a potent mix of frustration and hopelessness during this time, feeling drawn to their previous research into Irish political resistance in order to contextualise and, hopefully, cope with the developing, outwardly violent political climate.

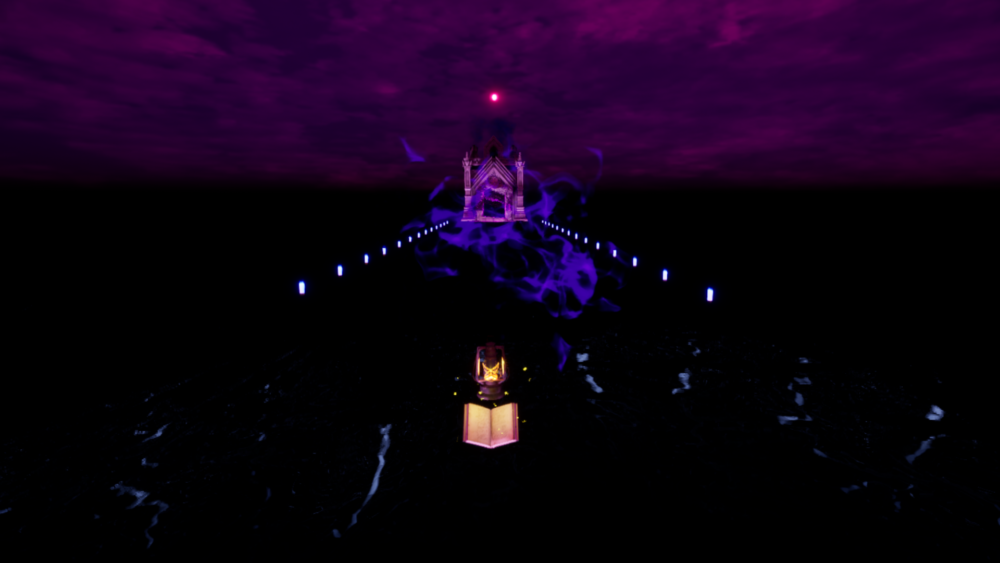

Thus, Bean Sidhe began development and was released in March 2025. Simple in concept and drawing parallels with games such as Gone Home, What Remains of Edith Finch and Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, Bean Sidhe is a walking simulator which features four Christian-style graveyards.

Beginning in a church, you first listen to the voice of the ‘bean sidhe’ (voiced by Candace McAfee) telling you that you are in the land between life and death, and that you are about to explore your ancestry. Exiting the building, you find yourself in a grave yard, tasked with moving between grave stones as you listen to the stories of those who lie beneath the earth, all emphasising Ireland’s resistance against British occupation and rule.

While drawing from O’Neil’s own family, Bean Sidhe also features fictionalised stories that serve as embodiments of O’Neil’s previous research on Irish history and their thoughts on the typical narratives they came across. Of particular interest is the story of Neil O’Broin from 1799 (voiced by Cai Kagawa), an imagined ancestor whose gravestone reads “[l]ived once, born twice.”

When asked about this moment, O’Neil explains that they designed Neil O’Broin as a pushback against the trend in historical narratives to erase queer identities, particularly trans identities: “I don’t want to just write cisgendered heterosexual experiences, because those are the only experiences that I’m reading about … [trans] people existed. I wanted to give these people voices when they otherwise wouldn’t have had them.”

Neil’s story highlights the experiences of documented Irish trans men such as James Barry, Patrick McCormack and Michael Dillon, whose exploration and expression of gender intertwines with, and is arguably inseparable from, Ireland’s fight for independence.

We hear that Neil, described as a member of the Defenders which was a Catholic secret society formed in the 1780s in County Armagh, threw the first stone at a group of Orange Order Unionists, a still-running organisation focussed on maintaining British rule on the island. In doing this, he became “one of the boys,” another male soldier dedicated to the fight for an Irish republic.

Neil’s story in Bean Sidhe not only highlights the sectarian violence that many were fighting in, and suffering through, at that time in Irish history, but also weaves in themes of queer identity and acceptance. The game raises questions about what it means to be accepted as a trans man, what conditions acceptance is potentially contingent on, and whether, in this case, Neil’s trans identity is dependent on his willingness to enact violence, justified or otherwise.

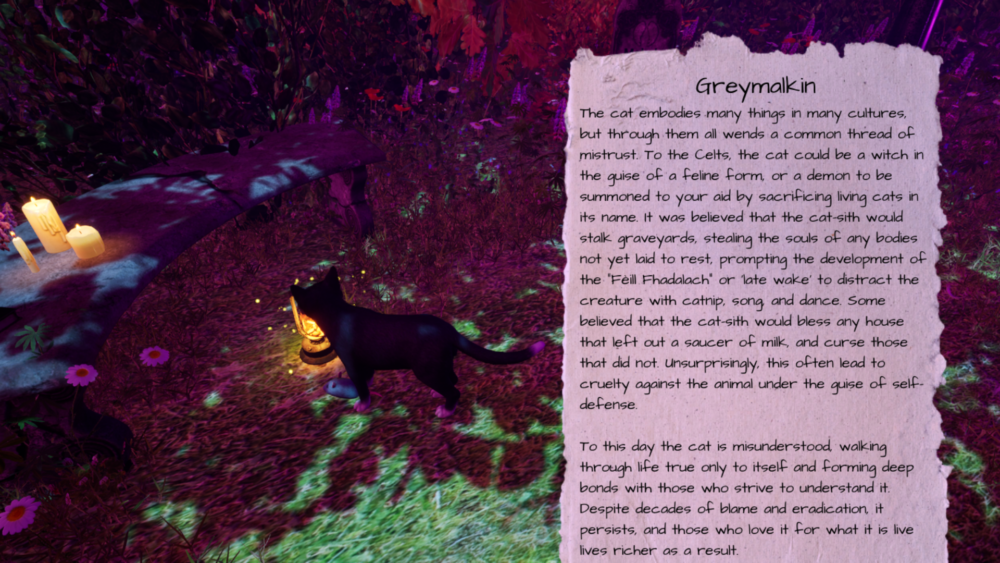

I focus here on Neil’s story as I think it exemplifies how Bean Sidhe weaves together various elements of queer identity and resistance in its exploration of Irish history. Alongside this though, elements of Irish folklore are also included.

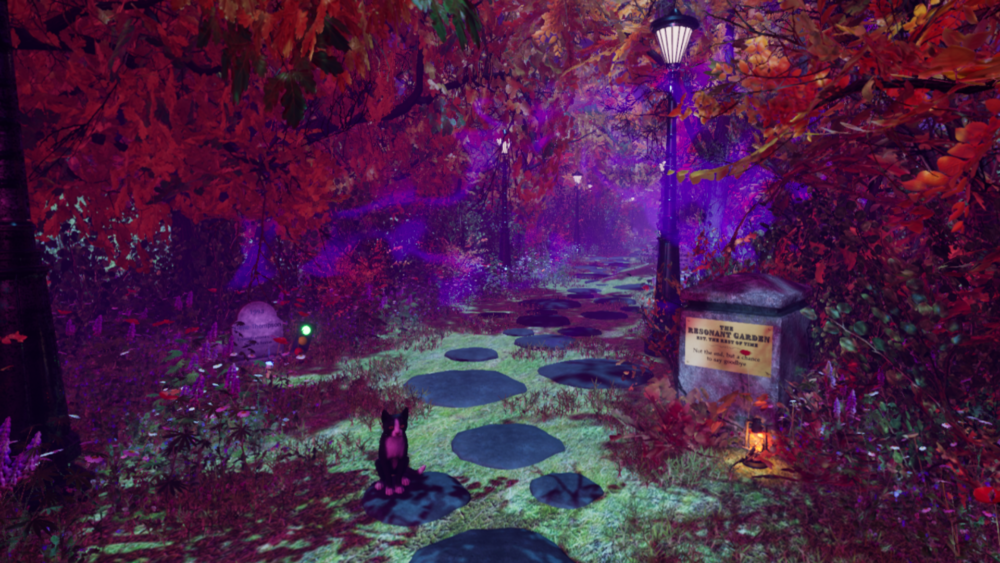

As mentioned, central to this is the bean sidhe, anglicised to banshee, a lamenting spirit typically depicted as a grieving, keening woman whose wails announce death. She exemplifies the game’s ever-present tension between religious adherence and folkloric tradition in Irish society, providing moments of reflection in the game’s various grave sites.

Moving through the various generations of O’Neil’s imagined ancestry in Bean Sidhe, the bean sidhe remains as a constant presence, constantly encouraging you to listen and bear witness to the stories you hear.

At its core, Sealbee’s Bean Sidhe is a game about heritage, death and resistance. Inspired by the BLM movement and drawing on their Irish heritage, lead-developer O’Neil uses Ireland’s history of struggle against British imperialism to present a game centred on solidarity and liberation.

In every aspect of its implementation, the game offers a model of queer resistance that is intersectional and situated, promoting a politics that has community at its core. By focussing on those that have come before us, Bean Sidhe reminds us not to be afraid to look back as we work our way towards a more liberated future.

Bean Sidhe is available now at sealbeegames.com, Steam and itch.io.