Ellie’s Story Offers Crucial Queer Representation, But The Last of Us TV Series Should Focus on Bill

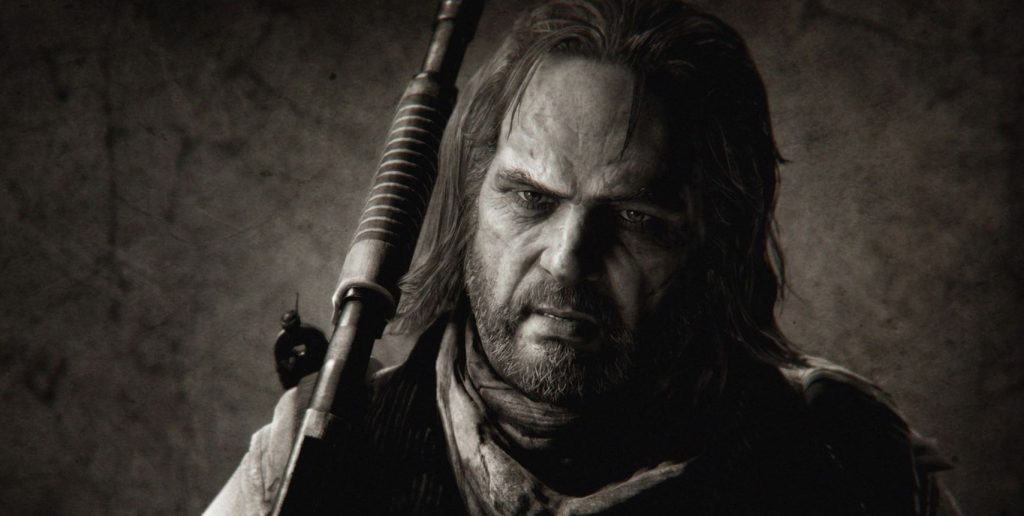

Ever since HBO’s The Last Of Us TV series was announced, the internet has been awash with casting choices. Kaitlyn Dever has shot out to an early lead as the fan’s pick for Ellie, while Hugh Jackman and Nikolaj Coster-Waldau have gotten the most traction for Joel, although Matthew Fox, Gerard Butler and the game’s voice actor Troy Baker have all been mentioned too.

We don’t know too much about the show yet, just that it’s set to follow the game’s major beats by centering on Joel and Ellie’s story in the aftermath of the outbreak. It’s also been directly confirmed from the show’s creator Craig Mazin (of Chernobyl fame) that Ellie will remain gay.

We sorely need more queer female heroines – and female heroines in general – so there is some cause for celebration in that. However, it just feels a little… hollow. Not in that Ellie is still gay, but in that, it’s still Ellie’s story at all. The Last Of Us is a deeply story-driven game and fleshes itself out even further with only modest player exploration. Added to that, the sequel releasing later this year also focuses on Ellie. While it’s a wonder to see a queer female heroine get so much spotlight, I can’t help but feel like they’re missing a much more interesting queer narrative by continuing to sideline Bill, a survivor who Ellie and Joel meet in-game.

Bill is my favourite type of gay character: His an asshole. TV and film have their fair share of gay best friends, badass action lesbians, queer coded villains, and gay heroes, but they don’t have too many assholes. Mac from It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia is a rare mainstream gay asshole, but when the premise of his show is that everyone’s an asshole, it dilutes the appeal somewhat. The reason I love gay assholes – no pun intended – is because they’re so searingly real. Bill is an unpleasant character for most of his short cameo in the game, yet through his rugged practicality and good but flawed heart, he forges a connection with the audience. Given more space to breathe, Bill’s story could flourish into something beautiful.

The Last Of Us is almost constantly tense; that’s one of its greatest strengths and a key reason why the giraffe scene is so peacefully powerful. An overlooked moment when this tension settles into stillness is when Joel and Bill walk in on Frank, suspended from the rafters, dead by suicide. Bill describes him as his “partner” after a loaded hesitation, and while we never get explicit confirmation of Frank’s sexuality the way we do Bill’s, it’s reasonable to assume the two were lovers.

By far Bill’s lowest moment of the brief time he spends with us, the story sticks the boot in even further, with Frank writing in his suicide note that he “hated Bill’s guts”. Theirs is a fraught, complex, wounding relationship and one which the TV series needs to use its extra breadth to focus on.

Ellie’s sexuality exists in a permanent state of post-apocalypse. As a young woman still discovering herself, her interactions with Riley in the aftermath of the zombies is her first experience as a queer woman. Love in the time of zombies has been explored before, and while queering it does lend a new perspective, it’s not nearly as fascinating as Bill’s. His sexuality straddles the before, during and after of the outbreak, and offers far more perspectives. As a gay mechanic in middle America who came of age during the Bush administration and the Don’t Ask Don’t Tell period of gay history, Bill’s story is deserving of an HBO drama even without the mushroom zombie context. The apocalypse was obviously a terrible, traumatic event, but perhaps for Bill, it had upsides. By ripping down the walls society had built up, we could argue that he was, in fact, perhaps freer to be himself.

That’s where his connection with Frank becomes even more enticing. Was Frank from a more accepting background? Did he and Bill’s divergent upbringing cause a culture clash? Maybe it was the opposite, and Bill couldn’t understand why Frank kept up barriers the zombies had already torn down. Maybe their differences had nothing to do with their backgrounds, but were just because, again, Bill is an asshole.

The point is, I want to know. I want to understand. I want to sway with every step and misstep of their relationship, I want to feel the pain so deep Frank etched the hatred into his own suicide note. Seeing Frank’s body was a shock the first time around, a hard thump to the chest in a game that already had my pulse racing. The second time though, I fear I still won’t even come close to understanding Frank’s journey into that noose, and it will all feel empty.

Ellie shares one beautiful last moment with her first love at the height of the zombie attack while she discovers her immunity to humanity’s affliction. She then goes on an action packed adventure with a pseudo father figure, culminating in him murdering the doctors who might have been able to create a vaccine, before lying to her about what he’s done and what she might be able to do for the world. It’s a brilliant story, no question, but I’ve heard it before. We’ve all heard it before. The Last of Us TV series might fill in some gaps, but it’s likely The Last Of Us II will beat it to the punch. I love Ellie, both as a character and for what she represents. I can’t wait to slip back into her shoes in the PS4 sequel, I but I already feel like I know her and her story well.

With Bill though? I hardly know him, and I desperately want to.