Comics Corner – The Greg Lockard Tapes, Part 1

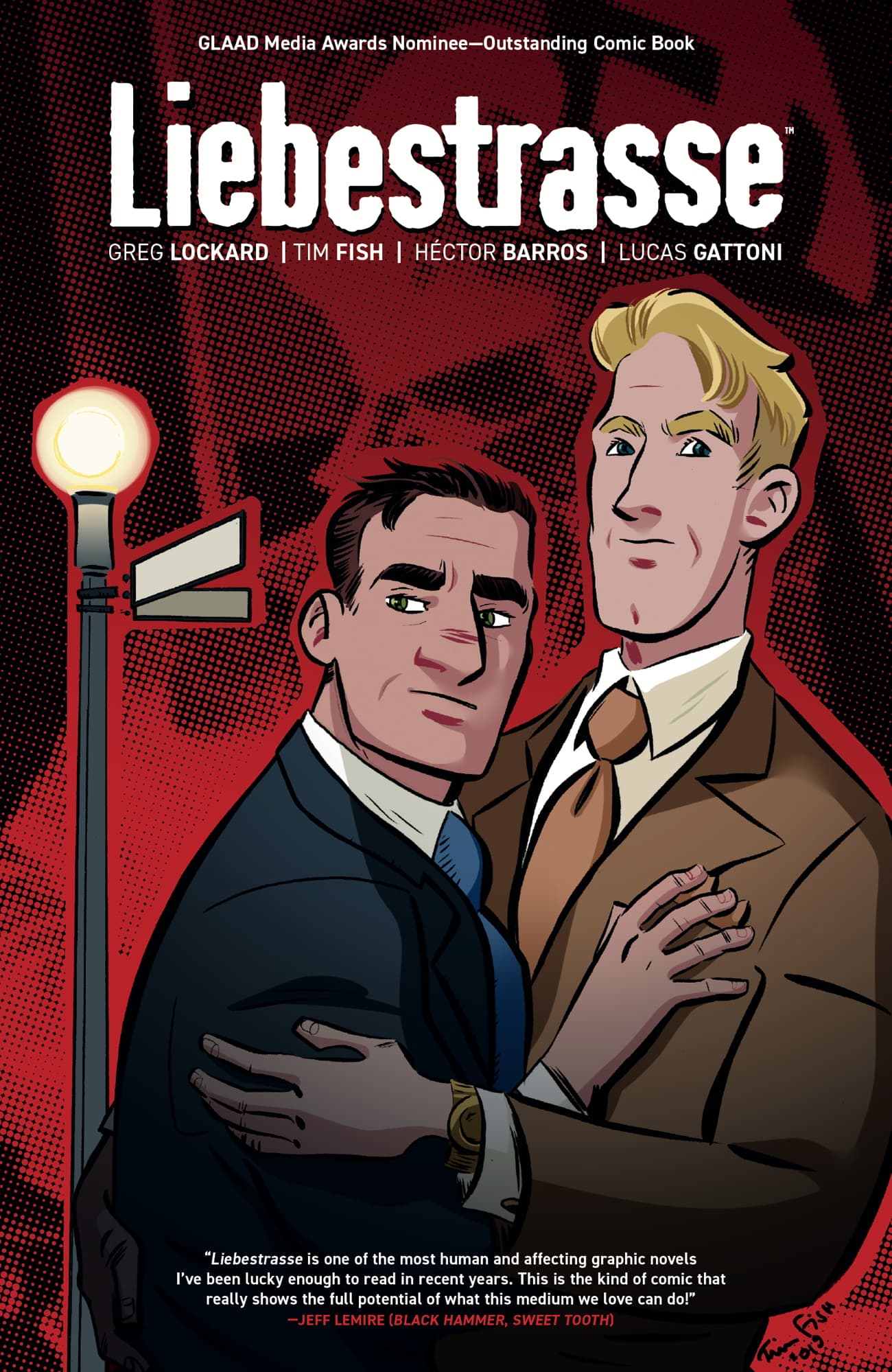

From intern at DC Comics to underground zine creator, to becoming an editor and writer in his own right, Greg Lockard has covered just about every facet of the comics industry in his career. After breaking through with his graphic novel Liebestrasse – a powerful and poignant historical gay romance, set in 1930s Germany as the Nazis rose to power, created with artist Tim Fish – Lockard has continued to explore LGBTQ+ relationships and identities.

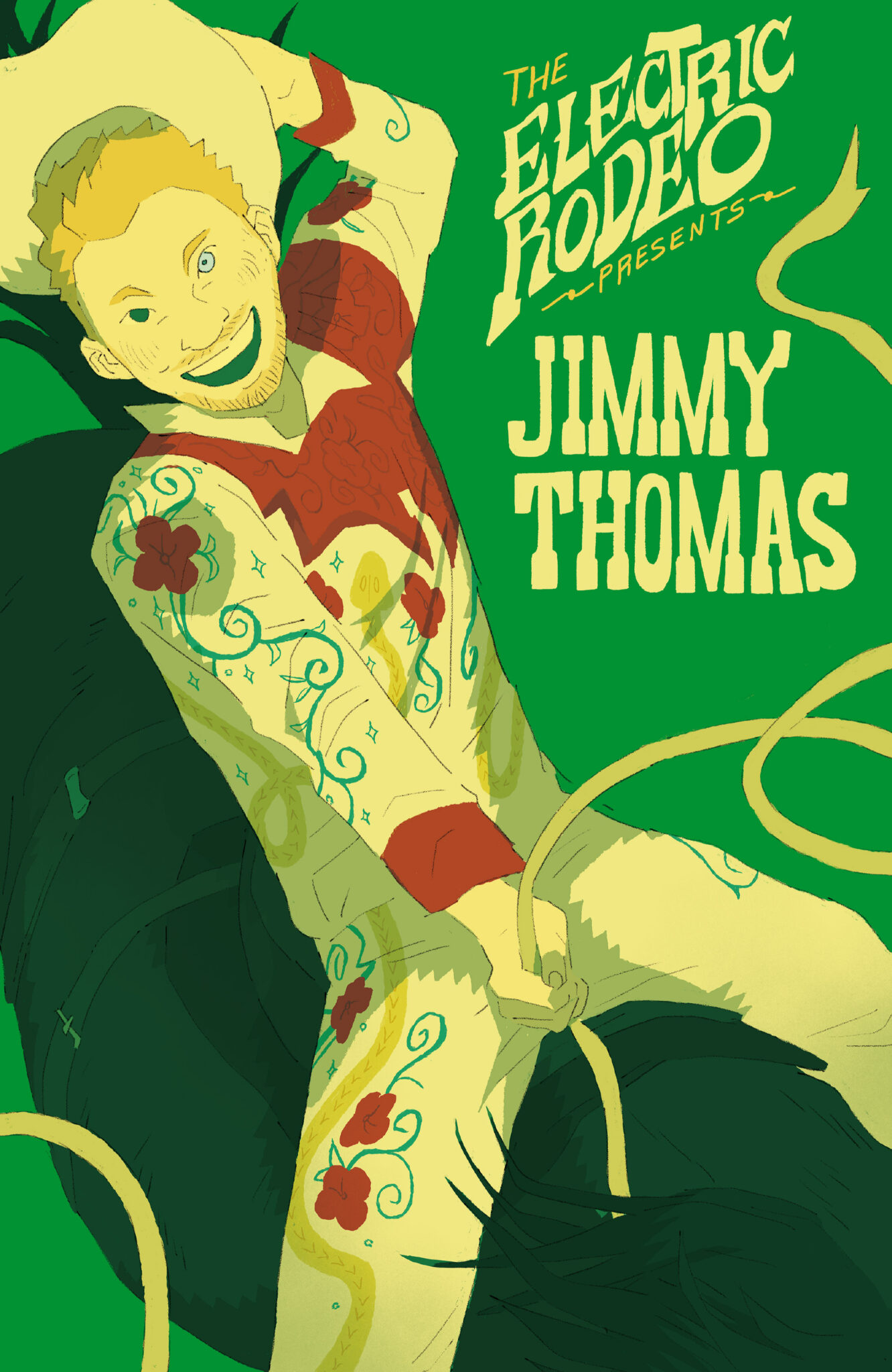

Lockard’s most recent work is Trick Pony, with Anna Bird on art. Mixing Western genre staples with psychedelic imagery and fairy tale influences, it’s a tale of fading rodeo star Jimmy Thomas, who takes an almost hallucinogenic horseback ride to his childhood home, hoping to confront the personal demons he’s spent a lifetime running from.

In the first part of our interview with Greg, we talk about his own comic book origin story, the inspirations behind both books, and the magic of comic books as a storytelling format.

Matt Kamen: Let’s start with everyone’s comic book favourite: origin stories. What first drew you to comics as a medium?

Greg Lockard: It was Betty and Veronica at the supermarket! Then when I was a pre-adolescent in the 90s, when the Marvel trading cards were a thing – the Fleer ones, with the Hildebrandt Brothers art – I was hooked. And then a lot of my friends in grade school were collecting them too, and that led me into the comic book store. I started reading the X-Men around that time, and pretty quickly gravitated towards creative teams. Peter David was writing X-Factor at that point and there was something about [his] writing that I just clicked with–

MK: I mean, that therapy issue, it’s timeless, right?

GL: Yeah, when anyone asks my favourite comic, that’s usually a big one. So yeah, that’s sort of my origin!

MK: When you shifted towards wanting to make comics for yourself, what made it feel like such a good medium to tell queer stories in?

GL: Well, queer stories were what made me feel like I could be like a creator. I was a DC Comics intern, and around that time Tim Fish was doing Young Bottoms in Love on Pop Image, and it was very early webcomics days. When I discovered that, I immediately became a Tim Fish fan. I’d see Tim out at MOCCA, which is a small press show here in New York – it’s a great show, it’s gone through a bunch of different versions and different leaderships. Fun fact: it was held in the building that Will and Grace used as the exterior for Grace’s apartment on the show, the Puck Building!

So I met Tim through that, and one of the other [DC] interns, Mike DiMotta, was an artist, and we did a short comic together for Tim on that anthology, Young Bottoms in Love. That was my first co-creation and first comic book story, and we made it into little zines. That’s where it started from, all these anthologies and short stories with Tim and Mike, and our other friend Monica Gallagher – it was queer stories from the start!

I guess I’ve always wanted to be a comic book writer and, throughout my career and the winding path that’s taken, I realised how special it is, when you have a chance to tell a story when you have a certain platform, and I definitely just wanted to tell those stories with the microphone while I had it.

MK: Getting onto Liebestrasse, which was your long-form breakthrough – a gay romance set between World War I and II isn’t perhaps the first thing you’d expect somebody who came to comics via the X-Men to be drawn to. What was the inspiration for that, and telling the story in a comic book style?

GL: The direct inspiration came from Tim. We’d worked on a bunch of short stories together [but] they were always more an excuse to like, make a zine or have a table at a show, and just sort of travel. We had gone to Thought Bubble with a couple of them, and were looking for something new, and Tim had this sketch – which ends up actually in the book – of this couple falling into bed. He had the start of a story in his head from his time visiting the memorials in Poland, the concentration camps. He said to me, “I’m a little stuck, let’s see what we can do with this”.

We started brainstorming – there is a very like long brainstorm and development period on that one, because it’s a really terrible subject matter [and] a really well-covered time, in world history and in pop culture. But we wanted to do justice to that hypothetical couple, and the queer people of that time that were murdered. It was a departure for me, in terms of seriousness and historical fiction and in those aspects, but it’s a period I love. I love old films and I love reading about that era. It’s a period of history that a lot of my favourite pop culture goes to, so it was pretty natural in terms of [doing] a piece of historical fiction.

MK: There’s a part in Liebestrasse where Philip’s friends are lamenting how dangerous things are getting, and how “every headline is worse than the last”. Given how we’re seeing regular attacks against marginalised communities in largely right-wing media in the present day, was that a conscious parallel or just unfortunate prescience?

GL: Yeah, it’s too real. It just ties in too closely to right now – you know, here [in the US] they’re actually writing laws to outlaw drag, and laws about medical care for children, and it’s all terrifyingly similar to have the lead up to all this. So that part, it does underline the importance – but I wish it wasn’t.

MK: Moving on to Trick Pony – the book feels like a big departure, tonally, narratively, and structurally. Did you have this surrealist/magical realist, weird, gay, rodeo, cowboy thing floating around your head already, or was it like an ayahuasca fever dream?

GL: I wish! The Grant Morrison approach! No, I mean it’s been in my head longer. The spark of it came from my first viewing of Robert Redford and Jane Fonda in The Electric Horseman. Trick Pony sort of starts in a similar way, where [in the film] Robert Redford is in this really garish, amazing, cowboy costume that has lights attached to it, and he’s in Las Vegas at a cheesy corporate thing as a spokesperson, just totally fed up, and he just rides the horse out of town. So it’s kind of germinating in my mind as a story that maybe would centre on a gay man in that world of rodeo and the American Southwest, but wouldn’t be just about a specific trauma or, you know, the stereotypical queerphobia or worse.

Then the surreal aspects were maybe more exaggerated or expanded upon during the production, and it’s maybe part of a fever dream – just sort of like the comic book version of this road trip. Somewhere between The Wizard of Oz and My Own Private Idaho.

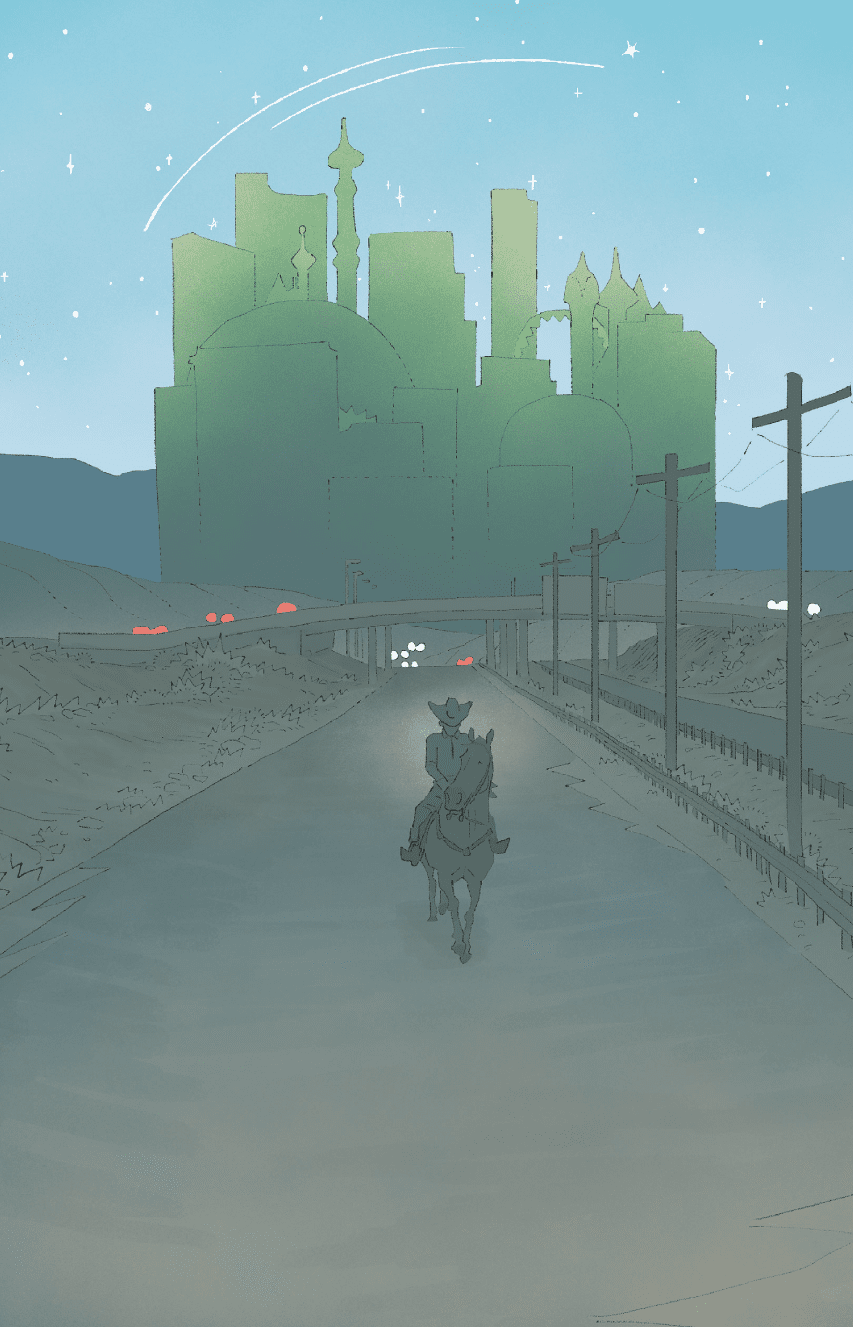

MK: I found the Oz parallels pretty potent, particularly the shot of Jimmy riding out of the ‘Emerald City’. Was any of that in the script, or was that from Anna’s influence as the project was developing?

GL: No, that was in the script. We were trying to build the city as sort of like an idealised Reno, Nevada, which is sort of like a smaller scale, more honkytonk Las Vegas; more retro. Just playing with that imagery of The Wizard of Oz, because I was using “it’s a reverse Wizard of Oz” as a shorthand to Anna, and to people as I was pitching it. That stuff was built in, just because that Oz imagery and symbols are just so inseparable from queer and gay identities that it was a good shorthand to get the readers into the world, to tell them that this wasn’t just going to be your standard Western road trip.

MK: How did Anna get involved with the book?

GL: Okay – so, horses are notoriously hard to draw, and the story was actually greenlit without an artist attached to it. So, once it was greenlit, I was sent out into the world by [publisher] comiXology, and I had some very abstract, unspecific ideas of what I wanted to look like, but I think generally – as an editor and as a writer – you have to give the artist room to discover the project and to make it their own. I don’t really lock into particular art style before then, but I had some ideas, and I wanted someone that could represent the queer aesthetic that this needed, to have that heartbeat.

I was going through friends and colleagues, talking to people, and one artist who I’m working with as an editor, V Gagnon is a younger artist and closer to art school. I was asking them for advice or if there was anyone in their circle that maybe just wasn’t on my radar, and told them a little bit about the story and V said, “oh, I think I have the person, a woman that went to art school with me and love horses, rides horses…”

I don’t know if she was working at a stable at that point or she had in the past, but I said, “oh, cool, send me her art samples, or put us in touch.” And Anna had a bunch of, like, demonic horses from Red Dead Redemption, and it was just an instant fit. Not that Emmylou, our horses is ever in danger of death, but yeah, zombie horses, I was like “that’s the look!”

MK: You wanted something a little bit unearthly?

GL: Yes, one thousand percent. Because I wanted the fantasy of this all was to take us all away. I spoke with Anna after V connected us, and Anna was very kind from the beginning, when it was a really rough story. I was purposely trying not to outline – I had the story, but I was trying not to do a very scientific or clean, organised outline. I thought the spirit of this project was to keep things loose and moveable and strange and dreamlike. So, Anna was very patient because it wasn’t a lot to go on in the beginning, and that’s why she was so able to shape so much, and answer questions that I had in the story that I didn’t know I had. It was really organic and wonderful when she came on board.

MK: “Dreamlike” is a term I used when I reviewed Trick Pony in Comics Corner recently, particularly with sequences like Jimmy meeting the drag queen Biz Bilmore, and it blurring from being a club setting to an aquatic world, and Biz inexplicably being a mermaid. What was the thinking behind those sort of mercurial, almost stream-of-consciousness scenes?

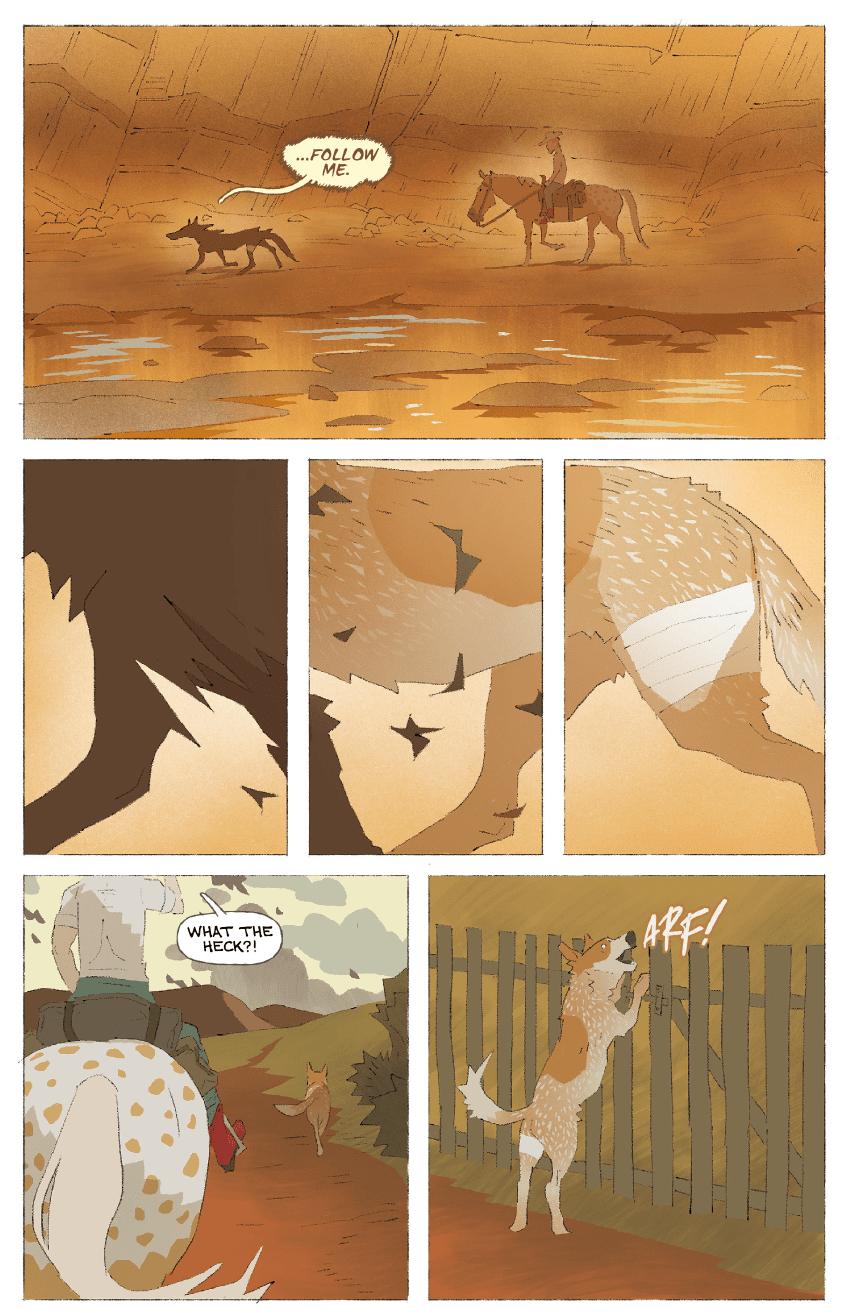

GL: Yeah, on the technical side I love the transitions in comic books. From page-to-page or panel-to-panel, there’s just so much magic in the sequential art form.

MK: Scott McCloud literally wrote a book about it, right?

GL: Yes, and I’ve unfortunately read it a couple of times! So utilising that magic, and letting the surreal aspects grow – and maybe that’s why it is surprising, because it was like “we have to take advantage of the medium, of Anna’s amazing artwork” in the transitions and the dream states. It allows you to do so much with the flow of the story that was just so much fun. But yes, I wanted it to bleed together, I wanted us to see exactly what Jimmy was seeing, but not have any narrative captioning so that we had to take everything at face value, and the reader can decide whether they think it’s a dream or a drug-induced hallucination, or if it’s just a comic book that has monsters in it. I just wanted all that on the reader, and to let their imagination just run with the story.

In part two of our conversation with Greg Lockard, we discuss finding optimism in queer narratives, gay superheroes, and how major publishers have become more accepting of LGBTQ+ comics over the decades.