Meet the mind behind the world’s very first VR LGBTQ+ museum

The world of technology is constantly changing, allowing for more inventive and creative way for marginalized communities around the world to express themselves, as well as share information and knowledge – which is exactly the case for the world’s very first VR LGBTQ+ museum.

Directed and produced by Antonia Forster and developed by Thomas Terkildsen, the VR LGBTQ+ museum was launched to the general public during the Tribeca Film Festival’s Immersive Exhibition from Friday 10 June to Sunday 19, 2022. Visitors were able to visit the exhibition in-person, or virtually through their own VR headset.

What made the museum such a big hit was that everything included was able to be interacted with, with those attending in-person able to do so while using the brand-new biometric features from Forster and Terkildsen’s DiVRse Technologies. These biometric features were controlled by users emotions in real-time, making each and every experience with the museum a unique one.

Being the very first VR LGBTQ+ museum, we sat down with Antonia Forster to learn more about the goings-on behind this virtual phenomenon, what inspired them to create this accessible place, and what comes next for the museum’s future.

What inspired you to create a virtual reality museum that not only celebrates LGBTQ+ history but personal LGBTQ+ history too?

I’ve always known that I’m LGBTQ+, but wasn’t able to come out of the closet until just a few years ago. When I did, it didn’t go smoothly – some members of my family responded with aggression, insults, threats, blackmail and even bribery. For my own safety, I had to cut contact with over half of my family, and we remain separated without contact to this day. I couldn’t help but feel that if they had been into a space like a museum – a prestigious space where we engage with culture that we deem appropriate, and worth platforming and preserving – but one that specifically celebrated, centred and normalised queer stories, that maybe they would have felt or acted differently. And maybe I, if I’d had access to such a space, would have felt less alone in that difficult journey.

Last year, I searched online to find out if there is a physical LGBTQ+ museum in the UK and was shocked to find there isn’t. I don’t have the resources or connections necessary to build a physical museum, but I do have the technical skills to build a virtual one. That’s where the journey began.

How have you made the museum accessible for everyone to attend?

The museum is designed in such a way that it’s equally accessible for people who are standing or sitting. For example, interactable objects are all at waist-height, there is a joystick-turn option for seated users (so there’s no need to physically turn your body around), and dropped items will reappear on their podiums. This facilitates access for wheelchair users, those with fatigue issues, or with certain mobility limitations.

The experience is subtitled, to accommodate D/deaf and Hard of Hearing users, or those that just prefer subtitling (e.g. some neurodivergent users, such as those with ADHD). Next, we would love to add multiple language options, additional accessibility features, and also create a “pancake”/flat version for those who don’t have VR HMDs – because VR headsets themselves, of course, present a barrier both in terms of financial and physical access.

You mention that you’re trying to disrupt historical gatekeeping, but could it not also be argued that VR is also a barrier? What are your thoughts about that?

Absolutely! I created this space in VR because I wanted, as closely as possible, to replicate the experience of being in a museum and seeing queer stories centred, celebrated and normalised in that setting. Our future roadmap involves creating a “pancake” / flat version of the museum that could be experienced via a regular PC – and potentially a web version, so that the museum could be more easily accessed. However, we’re a small team of marginalized creators, building this project in our “spare” time on top of full-time jobs, so we’re tackling one thing at a time!

How did you make it so that the art appeared and was programmed to respond to visitors’ emotions? And what was the purpose of tracking visitor’s emotions in the first place?

The content inside the museum itself is a combination of purely digital/virtual content (the museum environment, the podiums, the trees – and the digital artwork) and digital 3D scans of real, physical objects, which were created with a technique called photogrammetry.

For Tribeca, we added a biometric aspect – users wear a Shimmer Consensys GSR device which detects their heart rate and skin conductivity (which, taken together, are a good proxy for their level of emotional arousal/engagement). This drives VFX on a monitor as part of the physical display – what we called an “emotional portrait”. We used an Azure Kinect depth camera to capture the user and their movements visually, then display this as a sparkling avatar, and the colour and pulsing of that avatar is driven by the user’s biometric readings. The visuals change in real-time and are not interpreted (we don’t know which emotion people are feeling) or stored in any way, and we also don’t show what the user is looking at when they have these emotional reactions – in order to preserve their anonymity and privacy. The user can see their own emotional reactions while they’re inside the museum – the “emotional portrait” streams into the museum itself as an artwork – making the user part of the experience. The user is also surrounded by subtle glowing particles which change colour depending on their emotions, allowing them to monitor their own reactions as they explore the space and engage with all the stories and objects.

The reason we added this feature is two-fold. First, we wanted to highlight the common humanity that we all share – that no matter our demographic, we share the same common human emotions (often triggered by sharing stories), and how this forms the foundation of much allyship and affirmative action. Secondly, it’s a bridge to our next project, which focuses on how immersive technology can be used in combination with Compassion Cultivation Training principles, to deprogram prejudice in users and cultivate compassion towards marginalised groups.

The LGBTQ+ community gave you a lot of items to scan – will there be another iteration where items that aren’t part of this museum will be added in the future?

Absolutely. Our immediate plans for the museum, besides improving its accessibility, are to expand its “collection”. We would love to work with NGOs, enterprises, charities or local authorities (like city councils) to create bespoke versions of the museum that platform a subsection of LGBTQIA+ stories. For example, stories from their local queer community, or from a specific demographic (e.g. LGBTQ+ women, QTIPOC, queer people with disabilities or neurodivergence, trans folks, queer youth or elders), or around a certain topic (e.g. mental health, family, human rights).

The museum could then stage exhibitions specific to one theme or event (e.g. during Women’s History Month), or – once we have a large enough archive to choose from – could even give each user a choice. Unlike a physical museum, ours can grow limitlessly, and can be different for every individual. So I’d love to give each user the choice of what they’re most interested in – would they like to see stories from one location, or demographic, or theme, or a mix of everything? We found that people respond really strongly to seeing their own experience paralleled in a museum, particularly when they have never seen that before. But other users may want to specifically engage with stories unlike theirs, or have a mix of everything

What was the process of picking and choosing which items would be included in the LGBTQ+ museum?

It was very important to me that we had a diversity of voices and stories inside the museum. I reached out to several organizations I work with, including those that support specific intersectionality marginalised demographics, such as queer people of colour, or queer youth. I also reached out to friends, and put public shout-outs on several social media channels and groups. We ended up with an amazing diversity – stories from men, women and genderqueer people, cis and trans people, people of many different ethnicities, ages (mid-20s to mid-60s), and cultural experience.

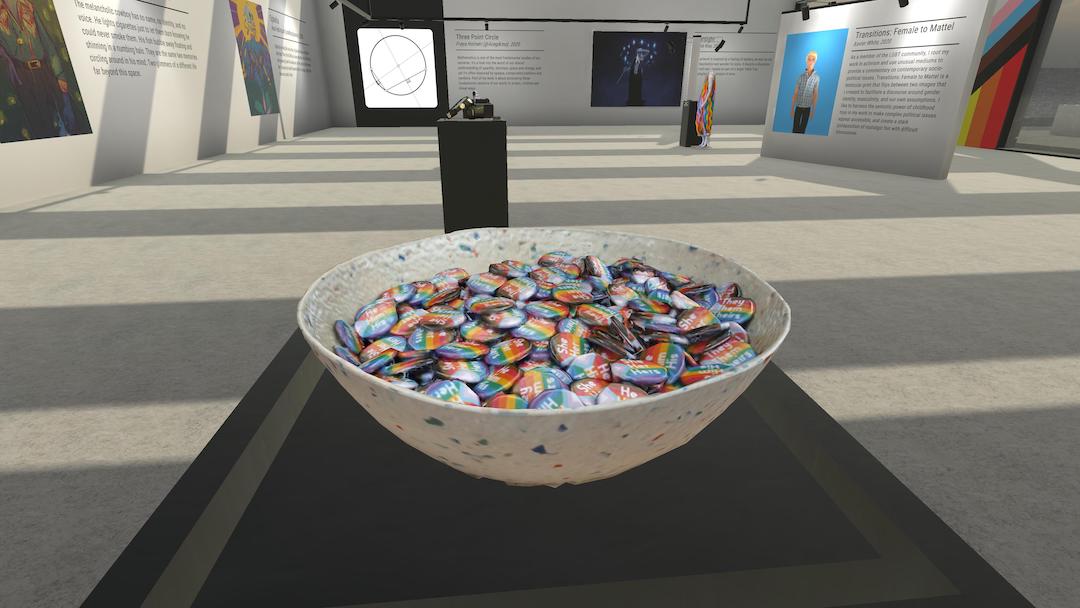

We gave the same question to each person – if you chose one object from your life to represent you in a museum, what would it be, and why? People chose a huge variety of objects, from a teddy bear, to nail polish, to pronoun badges, to a church pulpit, to wedding shoes (purchased by one woman’s girlfriend as a 40th birthday gift, before gay marriage was legal – and held onto without being worn for 20+ years, until it was finally legalised and they were married, when they were finally used). Each person shared the significance of that object in a short audio clip, in their own words (and voice), which can all be heard in the museum. So, in a sense, the museum was self-curating by the queer community itself.

The festival is now over, will this LGBTQ+ museum always be accessible?

Unfortunately, due to the rules around film festival eligibility, we’re not yet able to make the museum fully publicly available! However, we are now staging a number of exhibitions – in London, Cardiff, and hopefully across the world. We eventually plan on releasing the museum for everybody to access – either through an app store, or online.

Can you tell us more about the process of creating the museum, right from the very beginning to how it is right now?

I had the idea, and built an initial prototype in Unity, for the Quest 2. I built the first prototypes of the actual museum using ProBuilder. I added some photogrammetry-scanned objects from my room, and some basic mechanics (like an audio story triggered by a button in the museum, and the ability to grab and interact with the 3D-scanned objects), to create a proof of concept. I shared this on Twitter and it blew up, with people loving the idea and offering their skills to help, from music, to art, to helping clean up the photogrammy scans of assets. If you’re building something, I highly recommend sharing your work online, even in the early stages, so people can follow the journey and even join the project!

I ended up working closely with a Danish developer, Thomas Terkildsen, who totally re-designed the museum and became very much the co-creator and an equal partner on this project. He deserves complete credit for all of the biometric integration we added later.

Then we solicited stories and objects to platform in the museum, scanned them with a technique called photogrammetry – which involves taking hundreds of pictures of an object and using software to automatically stitch them into a 3D digital object – recorded people’s audio stories, sourced art to go into the museum, conducted user testing, changed the experience accordingly, debugged, and polished until it was done! Exhibiting at Tribeca demanded a huge number of additional tasks, including designing, producing and building the physical exhibit, but I’ll spare you the details. In short, it’s been an enormous amount of work!

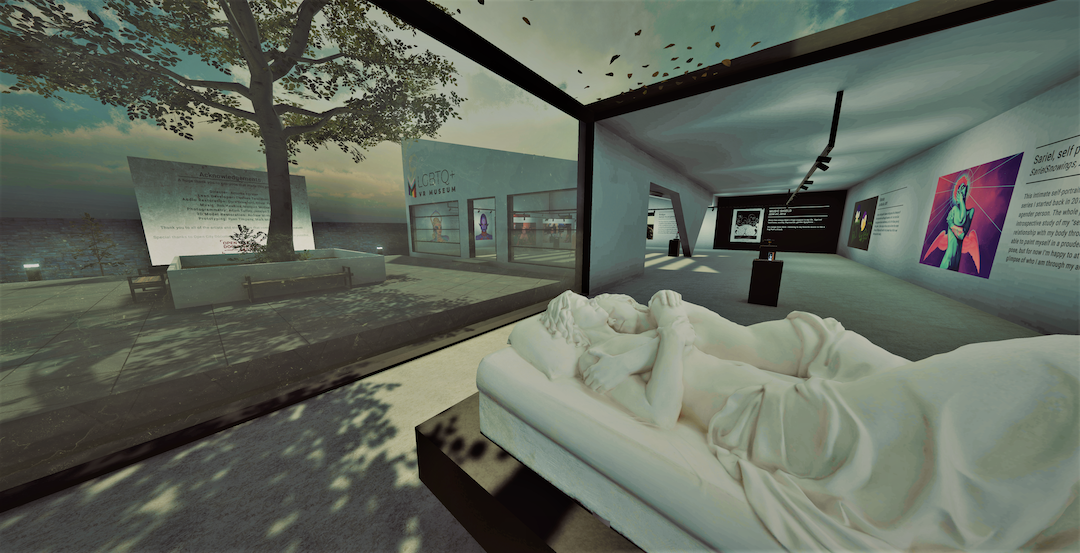

One 3D piece is Memorial to a Marriage – why was it so important to include this particular piece?

Memorial to a Marriage is the world’s first (and still only) monument to LGBTQ+ marriage equality. It’s a three-ton Carrera marble statue created by the renowned NY artist, Patricia Cronin. It depicts her and her now-wife, the artist Deborah Kass, holding each other in a gentle embrace and reclining on a bed, partly covered by a sheet, with their toes touching.

Patricia created this work in 2002, when gay marriage was not legal anywhere in the United States. At the time, the only official documents that officially acknowledged queer relationships – and gave some of the rights that marriage affords – were death documents, like a will or a power of attorney. So Patricia created this piece as a mortuary sculpture – to ensure that even if they did not receive equal acknowledgement of their relationship in life, they would have it forever in death. She purchased a burial plot in Woodlawn Cemetery, in the Bronx, and had the work installed there. (It has since been replaced with a bronze, while the original marble tours museums and galleries). Gay marriage is now legal in the USA, and Patricia and Deborah are married (and both still alive!), but the work remains an extremely important part of LGBTQ+ culture and history.

I have a deeply personal connection to this statue that came about by chance. I found out about it (on Tumblr, of all places) when I was a young teenager. I was still in the closet, and furtively using dial-up internet to search online for any information on being queer, and whether it was possible to be an LGBTQ+ adult (I lived in a homophobic household in a suburban area, and didn’t know a single openly LGBT adult at the time). When I discovered this statue, I was shocked. It felt like someone had reached out across space and time, taken my hand, and told me that I wasn’t alone. It was also the first depiction of a lesbian couple I had seen that wasn’t portrayed as seedy or sordid – it was elegant, beautiful, and romantic, exactly the way I perceived queer relationships to be. Representation – seeing oneself represented in culture – is so important for feeling affirmed, and coming to terms with one’s own identity.

I knew when I started building this museum that I wanted Memorial To A Marriage to be the centerpiece of the museum. I reached out on Twitter to see if anyone had connections to Patricia Cronin and, to my shock, she replied directly, saying she would love to be involved. I sent a friend of mine to Patricia’s studio in NY to take photographs, and produced the 3D asset that became the centerpiece of the museum. When we exhibited the work at Tribeca Film Festival in New York, I was finally able to meet Patricia in-person for the first time! She has been a huge advocate of the work – even attending the awards ceremony on my behalf when we won Tribeca’s New Voices Award (because I unfortunately caught COVID and couldn’t attend the ceremony)! It’s an enormous honor for us to have her incredibly culturally-important work as the centerpiece of our virtual space.

What are the plans for the future of the LGBTQ+ museum?

Right now, we want to create bespoke versions of the museum in order to expand and platform more stories (e.g. from one area, or a specific parts of the queer community) and work with museums/galleries and other venues to stage location-based exhibitions. Later, we want to add more accessibility features, like “pancake”/flat versions that can be accessed on normal monitors, and multilingual access. We’re potentially interested in creating other versions, like an online or multi-user version so that people can tour the museum in groups.

When we’re done with film festivals and touring / location-based exhibitions, we’d love to release the museum to be publicly available. And finally, we want to secure funding to expand our team, to make all this possible. Leads are much appreciated!

To find out more Antonia Forster, you can find her on Twitter.

If you’d like to keep up to date with the LGBTQ+ VR Museum, check out the project’s official website.