The Queer Paradise of Bugsnax

Bugsnax has quickly been labelled one of the most wholesome games of the year. Launching alongside the PS5, it pairs a cuddly cartoon artstyle with one hundred adorable snack-based creatures. While there is a little bit more going on beneath the surface as you explore Snaktooth Island and the village hub of Snaxburg, for the most part, it wears its wholesomeness on its sleeve. Its weird, mushroom-strawberry-sushi roll sleeve.

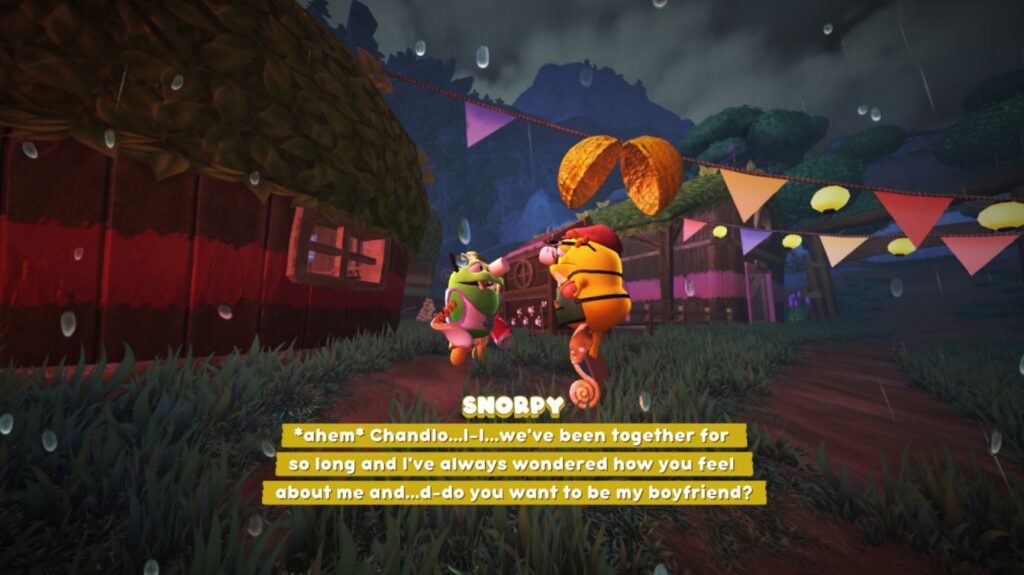

Bugsnax is also a queer game, and not in the “oh there’s a lot of speculation in the community that this character might be queer” sense either. In a cast of just 12, there are two queer couples versus one straight couple, with queerness not just present on the fringes, but important and explicit. Of the three relationships, the two queer ones also appear to be the two healthiest, one is the most central to the plot, and unlike other narratives with key queer relationships, there is no discrimination or hardship to overcome. Queer Grumpuses are allowed to flourish.

What is most interesting about Bugsnax’s queerness though is the way it blends being queer and wholesomeness together, and how it uses it to throw the spotlight on its protagonists rather than its titular half bug, half snack Bugsnax.

The game features 100 creatures who say nothing aside from muttering their own names, and is built upon a “gotta catch ‘em all” gameplay loop. The obvious comparison to draw then is with Pokemon, but playing it feels a lot closer to another Nintendo titan: Animal Crossing. The villagers are just that important to the overall experience of Bugsnax. Once I had gotten far enough through the game, I spent more and more time in Snaxburg completing side quests, talking to the characters, and experimenting by turning them into different ‘snax than I did rushing out to catch more Bugsnax.

It’s this focus on the villagers which makes Bugsnax’s queerness so important. We’ve slowly but surely been getting more queer narratives in games, but they’re often pushed off to the side or mired in tragedy. Queerness in games often comes through tertiary characters like Dragon Age: Inquisition’s Krem, or through lore alone such as with Overwatch’s Soldier 76. If the character is important to the story, their queerness often isn’t, while if queerness is central to a character’s essence, the whole character is often nudged off to the side. If they are brought into the middle, their queerness and their suffering are often indelible. In The Last Of Us Part II, transgender character Lev is occasionally deadnamed and his entire story revolves around the hurt and suffering being transgender causes, while leading queer couple Ellie and Dina are called slurs even in their own settlement, and in a world where everyone remembers Jurassic Park and Pearl Jam, nobody knows what the Pride flag means.

Even the more positive queer games are often rooted in pain. Indie hit If Found…, featuring trans characters and made by trans devs, has been praised for its positive themes, subject matter, and tone, but ultimately revolves around queer teenagers not being accepted in their own homes. If Found… is a fantastic game, one which tells a deeply personal, important, and necessary story. Far be it from me to suggest what it might have done differently to better serve the queer community. However, it’s very telling that a game so obviously built upon tragedy was universally praised as uplifting and wholesome.

This is frequent in wholesome games which feature queer characters, whether the queerness is as foundational as it is in If Found… or not. There’s always some throwaway line about problems with parents or at school or with old friends, always some issue or trauma which can be traced back to the character’s queerness. And I get it. Many of the real-life issues and traumas actual queer people have can also be traced back to queerness, and games want to be realistic and grounded, and relatable. But Bugsnax is a game where taking a bite out of a cheeseburger gives you curly fries for teeth. It doesn’t need to be realistic. It can just put the himbo with the mad scientist and tell you “they’re gay” and be done with it.

The setting of Snaktooth Islanditself is an important part of Bugsnax’s queer jigsaw too. It’s a mysterious island, and part of your job is to investigate why each character came in the first place. While many are fleeing certain problems or seeking new pastures, none of them are motivated by the negative side effects of queerness. The game allows queerness to exist without question or caveat, and lets queerness be part of its wholesomeness, rather than casting it in the role of rugged realism and asking it to prop the wholesomeness up.

Snaktooth Island is held together by Snaxburg, a village, a setting which typically screams “wholesome” but only whispers “queerness”, if it says it at all. The version of wholesomeness associated with villages is typically rose-tinted and non-intersectional. It’s a “good old days” wholesomeness, when everyone was nice and polite, where people could leave their doors unlocked, and where everyone was also white and straight. Most of the queerness we associate with Animal Crossing is invented, because queerness is viewed as something which could pollute the inherent wholesomeness of village life. Bugsnax inverts that, not only by giving us an uncompromisingly queer character, but by giving us four, and folding them right into the heart of the story. It challenges the notion of how queerness should exist in games, closely connects wholesomeness to queerness, and fights against the idea that queerness has no place in village life.

Bugsnax lets you become a walking shish kebab, a living french fry, or a vegetarian buffet, but it also lets you be something much more unusual: a queer person in a video game without trauma.