This Bed We Made and the threat on queer spaces

Picture it: Montreal, Canada, in the 1950s. As Sophie, a hotel maid at the Clarington Hotel, your job is to clean up and look after the guests’ rooms. Until one day, you discover something sinister: several of your guests are hiding something, and there’s a very good chance that someone’s about to get seriously injured. The mystery is a wadded knot, and This Bed We Made wants you to loosen the string until you get to the end of the thread.

From the black-and-white introductory scene, which follows Sophie walking into an interrogation room to give evidence on what happened at the hotel that day, it’s quickly established that we’re in trouble. Maurice, the detective, is only introduced momentarily before players are thrust into the colourful past, where we follow Sophie throughout the day and the events that will lead her to the daunting endgame.

Only, as it’s established by the end of the game, the mystery that developer Lowbirth Games wants you to unfold has everything to do with showing you a 1950s Canada in turmoil, fuelled by ‘homosexual deviancy.’ And how best to show that but in the Clarington Hotel, a space where privacy and secrecy can be bought?

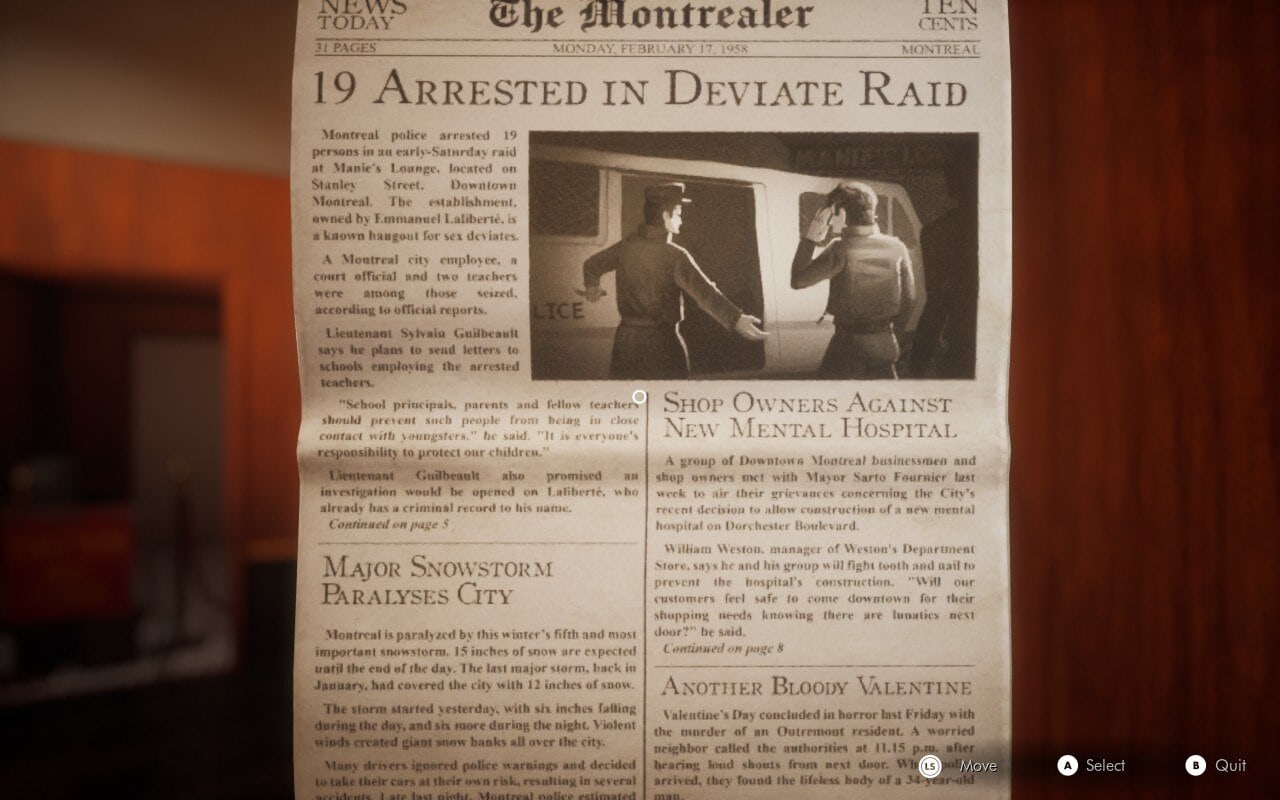

This Bed We Made takes place in 1958, a whole 11 years before Canada’s Bill C-150 (Criminal Law Amendment Act) was passed to decriminalize homosexual relationships. Before that bill was passed, however, homosexual men and women (with a focus mostly being on the former) were often branded as deviants and given an indeterminate amount of jail time. This context runs through the entire story of This Bed We Made. One of the first items that Sophie can examine is a local newspaper detailing an arrest of a group of people at a bar, which gives special mention that the ‘sexual deviants’ that were arrested were school teachers and people in government. Ironically, this is right next to a leaflet that demonizes divorce stuck up by Sophie’s boss, Linda, who Sophie can discover is cheating on her husband with the owner of the hotel, Bernard.

As a hotel maid that her boss doesn’t appreciate, Sophie is on the lowest rung on the ladder at the Clarington Hotel, but this has its advantages. For one, she can flitter from space to space to clear away the remnants of what the guests (and her colleagues, if she so chooses) have left behind — whether it be something as personal as a love letter or something mundane, like cigarettes. She can also snoop through their things, leading her to realize that a lot of the rooms she’s cleaning belong to queer men and women who use the hotel as a personal and private safe space.

In transitional spaces such as an airport or, in the case of This Bed We Made, a hotel, blending into the crowd as just another name on a piece of paper is the cloak that affords marginalized people some much-needed brevity. For the Clarington Hotel, players learn that this safety is actually what draws queer men and women to it in the first place.

Or at least it used to. While cleaning Bernard’s office, Sophie discovers that he bought the hotel from his brother and aims to clean it of its previous ‘depravity.’ What was once a non-place where queer people could find anonymity is now being actively threatened by a powerful, bigoted man who wants to do nothing more but crush it underfoot.

While Bernard tries to keep a hold on his ‘ailing’ hotel and cleanse it of the rot that he believes clings to his brother, he cannot prevent his guests from being themselves as soon as that door is shut and the lock turns.

In Room 507, two women exchange notes by code about meeting one another when the other’s husband is away, and the other’s child is asleep. In 505, a man reaches out to an old friend who possesses his heart, only to find out it is too late to make that connection through his dead love’s mother. In 506, two women scribble notes of mirth and affection to one another, while in the drawer that separates two beds (with only one rumpled and used) lies a forgotten birthday card from a husband wishing his soon-to-be wife well. On the floor is a leaflet advertising the Clarington Hotel’s Valentine’s Day ball, the hair of the man scribbled on to become longer and feminine.

Even Sophie, who you can choose as someone who also has had same-sex relationships and attraction, alongside fellow colleague Beth, plays a monumental role in showing how their jobs at the hotel is an imperfect but meaningful place for them to mingle alongside a dominantly heteronormative society. For Beth, her good looks and street smarts allow her to get away with her domineering behaviour that wouldn’t have been considered acceptable for women during a time when women’s roles were still being scrutinized after World War 2. Her beauty also allows her to get away with how she dresses as a receptionist, with a tie, dress jacket, and pants, a look far more masculine than all the other female characters you see.

But what truly sells just how significant these non-places are is to contrast what they mean to marginalized people in the 1950s to what they mean to characters who also use them, such as Linda and Bernard. As mentioned previously, Sophie discovers the two are having an affair despite both already being married. Much like those whom they oppress, Bernard and Linda use the hotel to find safety to commit adultery, something which would also been considered ‘deviant’ by religious institutions during that time period. In their desire to strip away that safety net from these communities that don’t align with their own beliefs, Bernard and Linda expose themselves as hypocrites.

With all the puzzle pieces coming together, about the queer guests and the overwhelmingly homophobic landscape that awaits them outside of their hotel room, Sophie is given a level of control that makes her a force to be reckoned with. Her colleagues and boss may see her as nothing but a ghost, insignificant and small, but she has the potential to steer the police investigation in several different ways. Will she leave the evidence that incriminates her community, or will she remain unseen as she removes evidence that puts her guests in danger? Ultimately, the choice is up to the player, which adds a level of variation to the endings that will, as it did me, make you want to go back for a second and even a third run.

Yet, regardless of your ending, what This Bed We Made leaves players with is an undeniable truth that has remained consistent throughout history: bigotry cannot stop love, no matter how hard it tries.

This Bed We Made is available to play now on PC.