Comics Corner – Doctor Strange just transcended gender to save the Marvel Universe

A year ago, Doctor Stephen Strange died. Given that Strange was Master of the Mystic Arts and no stranger to travelling ethereal realms – not to mention, this is comic books we’re talking about – that wasn’t as permanent a departure from the mortal plane as it would be for us. However, it still meant that, for a time at least, Earth was left without its Sorcerer Supreme.

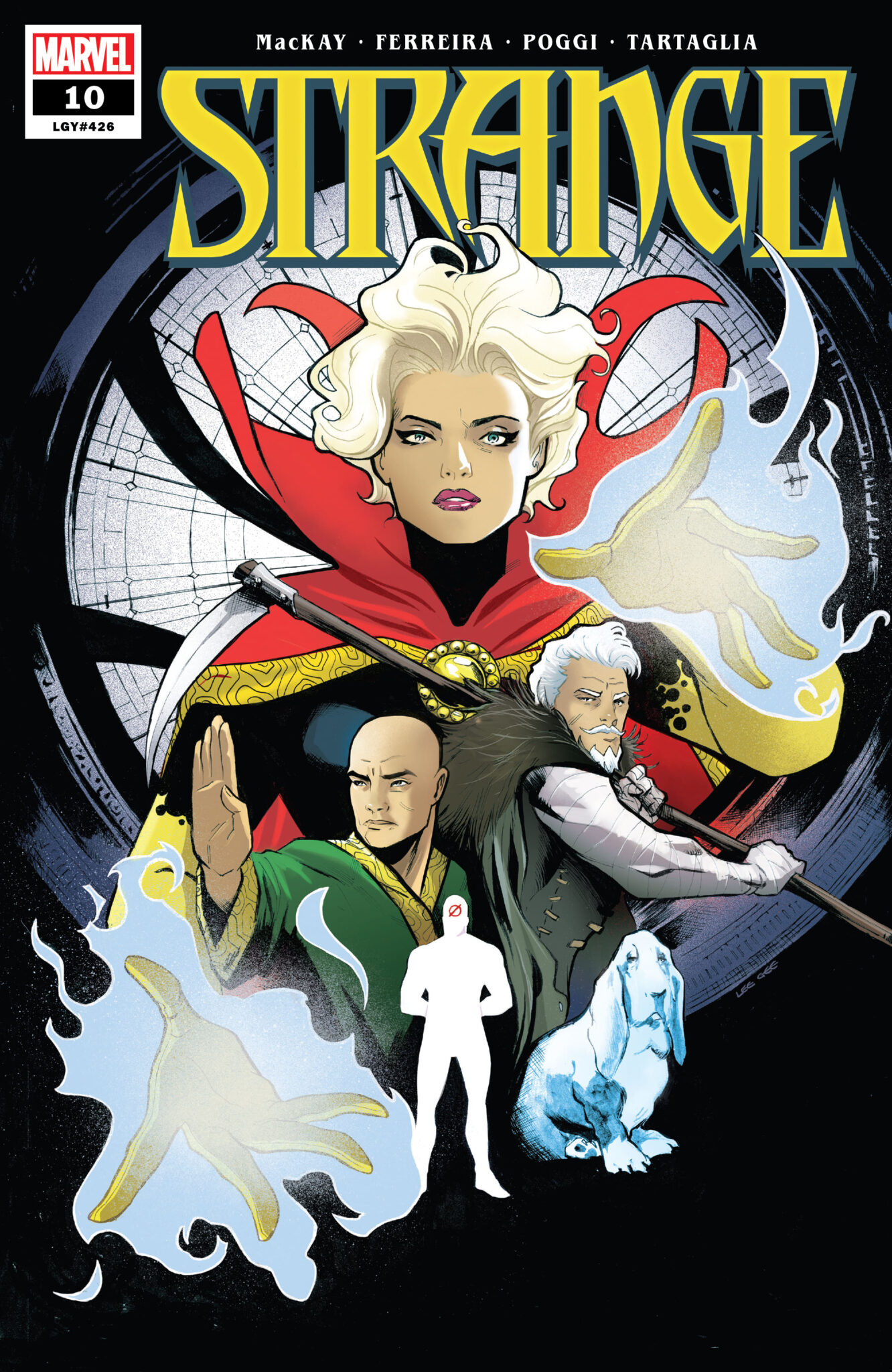

As of this week though, the good Doctor is back, returned to the land of the living in the pages of Strange #10, written by Jed MacKay, with art by Marcelo Ferreira, Roberto Poggi, and Java Tartaglia. This was no mere superhero resurrection though – his return was heralded by one of the queerest moments (albeit possibly unintentionally so) in recent Marvel comics history.

Backstory time: in the wake of The Death of Doctor Strange (also written by MacKay, with art by Lee Garbet and Antonio Fabela), Stephen’s wife Clea stepped into his former role, taking on the mantle of Earth’s premier magical defender. Already the Sorcerer Supreme of her native Dark Dimension, adopting her husband’s powers and mantle made Clea arguably the strongest Sorcerer Supreme to date.

The ensuing Strange series explored Clea’s differing approach to the role and responsibilities she’d inherited. Where Stephen was very much a Doctor in every sense, treating magical maladies and interplanar infections much as he did medical problems when he was a conventional surgeon, Clea’s heritage is from a line of interdimensional warlords. As such, she was far more direct and proactive than Stephen – in her own words, “far more brutal”, even cowing Doctor Doom when he tried to claim the title of Sorcerer Supreme for himself. Knowing herself how mercurial death can be for people in her line of work, Clea also pre-emptively set up magical alerts should anyone return from death, hoping to be alerted to Stephen’s likely inevitable resurrection.

However, the main arc of Strange saw Clea battling against a new threat called the Blasphemy Cartel, a terrorist organisation using twisted magics to revive deceased superheroes as powerful Revenants, ramaging zombies to be aimed at the Cartel’s targets. Tackling these Revenants brought Clea into conflict with another threat, the Harvestman – a gold-masked warrior of Death herself, armed with necromantic spells and an intimidating scythe.

As the series progressed, it was revealed – perhaps unsurprisingly – that the Harvestman was in fact Stephen Strange, tasked to stop the creation of Revenants, which were seen by Death as an affront to her authority. Unfortunately, it was no happy reunion for the Stranges, as Clea’s role made her the avatar of life, while Stephen’s was one of death. Should the pair even touch, it would be disastrous.

Short version? They touch. Faced with the most powerful Revenant that could possibly be created – the reanimated Sentry, a being said to possess the power of “a million exploding suns” in life, but now compossed of “one hundred million screaming ghosts” in death – Clea and Stephen break all the rules and kiss. As their conflicting natures rage, Clea – through sheer force of will, stubbornness, and love – takes over the reaction and uses their opposing states to create not destruction, but an almighty new being.

Simply known as Strange, the entity is a composite of everything Clea and Stephen are, combining their opposing attributes into a singular form. While the spectacle is suitably cosmic in approach – helped by Ferreira’s brilliant design for Strange, presenting a four-armed, four-eyed near-deity bearing Doctor Strange’s iconic Cloak of Levitation and Eye of Agamotto, plus Clea’s Flames of the Faltine, all wrapped up in a body that seems to contain the universe itself – the most interesting aspect is that the gestalt being is beyond gender or sex.

In the wake of the combination, Strange refers to themself as simultaneously existing as each of their component aspects. Life/Death, Light/Dark, Faltine/Human, yes – but also Woman/Man. Not only is that both extremes of the gender spectrum at once, but presumably also encapsulates every stage between them. And, faced with the unstoppable power of the Revenant Sentry, the being that is Strange, both genderless and of every gender, realises “we are its equal”, handily dispatching their foe and restoring some measure of peace to the fallen hero, while also dismantling the Blasphemy Cartel.

It’s not the first time comics have seen such fusions resulting in powerful beings that transcend gender. Perhaps most notably, in their run on DC’s Doom Patrol, writer Grant Morrison evolved the character Negative Man into Rebis, also a gestalt being formed of male and female individuals – there Larry Trainor, the original Negative Man, and physician Eleanor Poole. However, in Rebis’ case, the fusion was unwilling, instigated by the “Negative Spirit” that gave Trainor his powers, and internally unstable, as the component people were at odds over their situation.

Such contrast to the likes of Rebis is what makes the composite Strange so great though. While MacKay was perhaps not intending Clea and Stephen’s merger as an explicitly queer moment, the fact that Strange was brought into being willingly and as an act of love, and then proves to be a phenomenally powerful force for good, is likely to have far deeper meaning and importance for genderqueer people.

Whether Strange will be seen again remains unknown – and the fusion may prove to be a one-time merger attainable only because Stephen was an avatar of death at the time, and is now restored to life. However, a new volume of Doctor Strange launches in May 2023 (with MacKay continuing to write, joined by Pasqual Ferry on art) and while the headline focus returns to Stephen, Clea will remain a key figure in the series. Readers may discover whether the genderless, godlike Strange remains a tool in Clea’s and Stephen’s armoury there, but even if not, their appearance remains a moment that genderqueer readers of all stripes may be able to find some positive, powerful representation in.