LGBTQ Gaming in Iran – A Community Fighting for Survival

Being a gamer, a queer person, and an Iranian tends to be an odd combination, especially to those in Western countries. When I talk about myself, people wonder if anyone in Iran can play video games or if there are LGBTQ people in the country. Iran’s ex-president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, didn’t help with this when he said, “there are no gay people in Iran; I don’t know who told you there are any.”

However, I can assure you that we do exist, and we do play video games.

Iran has a long, complicated, and fascinating history with regard to the video game industry and the LGBT+ community.

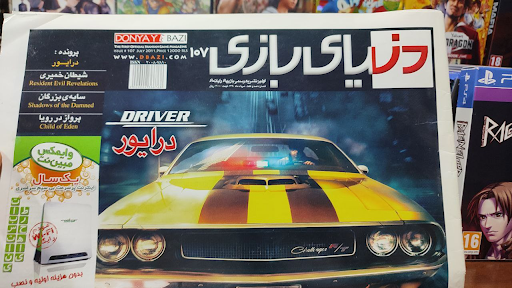

Iran’s relationship with video games goes as far back as the 1970s. We don’t know a ton about gaming during the Persian monarchy, but we know, based on surviving newspapers that Iranian tech companies made replicas of American consoles such as Magnavox Odyssey. Although, it wasn’t accessible to most people.

Since the revolution, video games have either been frowned upon as a form of western/eastern degeneracy by the government, or have been adopted into propaganda pieces for domestic usage. Yet despite the censorship, maddening sanctions, and ever-growing isolation, Iranians have been able to find ways to play, write about, and develop games.

It is said that there are more than 42 million gamers in Iran, and as an Iranian, I don’t find this estimate far-fetched. It is most certainly difficult to be a gamer or work in the game industry, but it’s not impossible, and much like how Iranian women have found ways to ditch the compulsory hijab in creative ways, Iranian gamers have found creative ways such as using retailers and meddling proxies to get their hands on games.

These days, gaming has become part of the Iranian pop culture, and I do not feel ashamed to say I study game design and write about games. Though, being an LGBT+ gamer is a whole other story.

Iran’s relationship with LGBTQ+ culture is much longer than its history with video games and, in many ways, far more troubled. Despite Ahmadinejad’s strange claim that I mentioned earlier, LGBTQ+ people have been very apparent in Iran’s history and culture. Persian literature includes a significant amount of homoeroticism and gay themes to the point that it would be literally impossible to write about Persian literature without bringing up some poems about gay love. A few examples are Rumi, Sa’adi, and Hafez, who constantly wrote about their male lovers. Believe me; I’m not exaggerating. I grew up in the highly homophobic Islamic schools of the current regime, and even they were unable to exclude these pieces of literature.

In the first year of elementary school, I played Final Fantasy VII. I took control of an atypical protagonist who didn’t exactly fit in with my perception of what a manly hero should look like. The game went on to break my perception and understanding of gender when Cloud was forced to cross-dress in order to make his journey progress – a scene that was very well-adapted in the Remake. With moments like this, it’s not an exaggeration to say games have encouraged me to think deeper about my identity and be able to express myself much more authentically. For years, they have been the primary force for me, as a queer person, to understand I’m not a freak, to understand I can be beautiful, confident, and powerful, to understand I don’t have to follow the footsteps of the poorly constructed idealized hypermasculine figures that are propagated in every other aspect of my life.

For the longest time, I thought I was alone in my seemingly rare connection to video games. However, as I grew older, I was able to find many LGBT+ gamers who shared similar experiences, and all of them had told me that their sexuality and/or gender identity had been interconnected with their gaming life.

“I always thought games are all about guns and big stinky dudes fighting each other,” says Sahar, a 25-year-old pansexual university student. “It wasn’t until I tried out Nier that my attitude shifted. I couldn’t believe it that the main female character didn’t fall in love with the protagonist, and there were so many hints that, in fact, Emil [a male character in the game] is attracted to the protagonist. People tend to downplay representation in games, but they are so massively powerful for minorities who are living in countries like Iran and don’t have access to anything that would validate their being.”

I talked with more than twenty LGBTQ+ gamers in Iran, and many of them told me that representation in games had given them insight into what it means to be part of the LGBTQ+ community. These types of anecdotes are especially apparent for people like Sahar, who grew up in a time when the internet wasn’t as massively used in Iran as it is today.

While talking to people, I found myself curious about the type of games that is mostly well-loved by LGBTQ+ gamers in Iran, and I think beside one exception, everyone believed that role-playing games had a significant impact on them with regards to expressing their gender identity and/or sexual orientation in an environment in which doing so would be considered taboo at best and at worse, a crime punishable by death.

“Role-playing games opened up a world of potential to me,” says Reza, a gay content creator, and podcaster. “Every time I play role-playing games, I’d try to find out if I could romance a same-sex character, and these small aspects have always helped me cope with the harsh reality I am living in. RPG games are like a breath of fresh air when you have to deny your existence 24/7. That’s the main reason I love to play and produce content about such games.”

Another interesting element I was faced with during my research was the amount of love that the Iranian LGBT+ gamers have for eastern/Japanese games. The weeaboo culture in the West is not necessarily known for its tolerance. However, in Iran, there seems to be a strong correlation between people who love Japanese-produced media and LGBTQ+ geeks and gamers.

“Even though there is a fetishizing element to BL visual novels, they became the primary force for me to find out more about myself and the broader LGBT+ family,” says Mahdi, a 25-year-old gay soldier. Mahdi and many others told me that the aesthetics, themes, and characters of Japanese (and, to some extent, Chinese and Korean) games not only made it easier for them to escape from the reality of the heteronormative society they lived in, but also have created some of the most welcoming and inclusive fandoms in which they could openly express themselves and find friends.

Unfortunately, these inclusive fandoms have attracted a lot of attention from a certain group of people in Iran. If you search the term LaGBaT (a modern derogatory term to describe LGBT+ culture) on Persian-speaking social media platforms, such as Telegram, you’ll find a disturbing number of groups, channels, pages, etc., dedicated to hating and threatening LGBT+ people. A new imported form of queerphobia that is almost always accompanied by sinophobia and racist sentiments.

“An empire that used to rule east Asia [Japan] has become a weak shelter for men who look like women,” reads a tweet from a far-right account that is part of a newborn political movement that worships the strong men of the west, such as Donald Trump, and sees LGBT+ rights as a leftist agenda which aims to weaken Asian countries, including Iran.

One might say Iran has its own Gamergate cultural wave. It is especially disturbing since LGBT+ people haven’t had it easy for decades, but many conservatives are importing new forms of hatred from outside. Shaghayegh, a 27-year-old trans engineer, believes that the Iranian gaming communities have become especially hostile towards transgender people.

“In recent years, I have been observing a rampant surge in hatred against trans people, even among those who identified themselves as LGBT+ allies,” Shaghayegh says. “This seems to be an importation of anti-trans media that has been produced at a staggering pace in the West. Something [being trans] that had been somewhat accepted, is now seen as a destructive force that deserves immeasurable hatred.”

The state’s historically hateful attitude to gay people does cultivate waves that make it harder for LGBTQ+ people to engage and become more visible in society. However, despite the extreme hardship, many of the people I talked to seem hopeful and told me that thanks to the power of the internet, they’ve been able to find friends and create groups in which they could be themselves.

“I will never forget the moment when the Editor-in-Chief of one of the magazines I used to work for fired a homophobe who was explicitly harassing me. He did this despite knowing that it might cause him trouble in the future,” Reza says. “These rare moments make me think that the future might not be as gloomy as it seems. After years and years of being suppressed, you eventually develop a natural skill to find the right people and groups and avoid situations which could harm you.”

Iran’s troubled history with gaming and the LGBTQ+ community tells me that everything can change. Most of these changes in Iran might not have been great in the past, but just like how a country with the richest gay literature in the world became a highly homophobic one, I believe significant progress can also be made. The LGBT+ gamers I spoke to showed me that to survive; we need to be hopeful. Societies change, and we need to find ways to adapt and yearn for a better future.