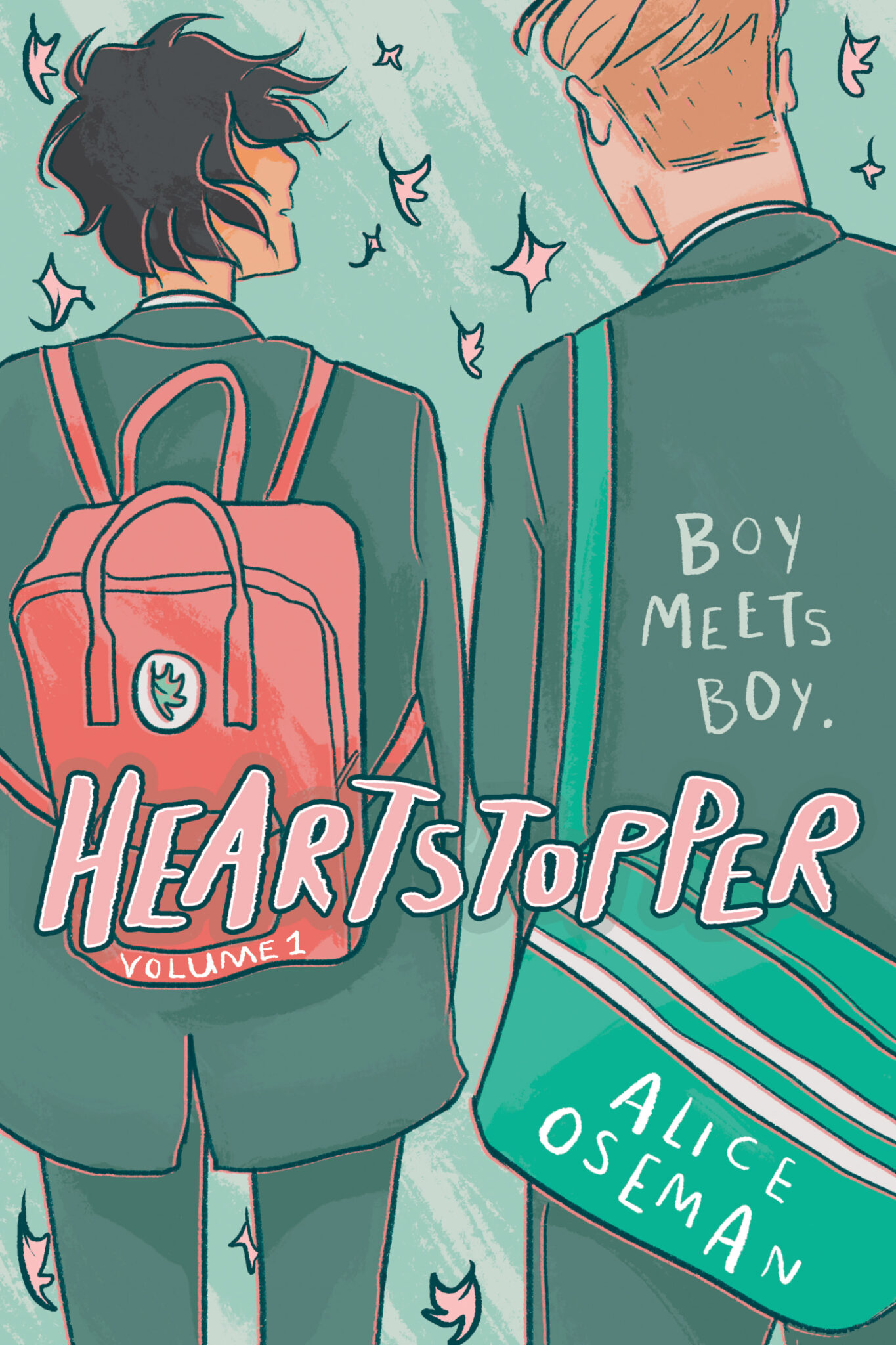

Comics Corner – ‘Heartstopper’ is Netflix gold, but don’t sleep on the original graphic novels

Heartstopper is the biggest show on Netflix right now – and deservedly so. A wonderful, heartfelt coming-of-age teen drama, the series focuses on the blossoming romance between two boys at a British grammar school – Charlie Spring, a year 10 student and the only openly gay boy at Truham High, and Nick Nelson, a year older than Charlie and the “Rugby King” of the school, who finds himself questioning his identity as he begins falling for Charlie.

The series delights thanks to sparkly dialogue and perfectly pitched emotional resonance that captures every last stomach-flipping, uncertain, awkwardly exciting moment of young love. It also boasts incredible performances from a cast that includes a wealth of young LGBTQ+ talent, alongside the likes of Oscar-winning legend Olivia Colman.Yet while the show is getting all eyes on it, fans shouldn’t ignore the original comic the series is based on.

Heartstopper is the work of Alice Oseman, who launched the series online in September 2016. However, Nick and Charlie had first appeared in one of Oseman’s prose novels for young adults, her debut work Solitaire. In the book, Charlie was the younger brother of protagonist Tori, and already dating Nick. While neither were major characters, they stuck in Oseman’s mind, forming the basis for what would – after years of trial and error – become the 2016 webcomic.

It became a hit, with Oseman’s story not only greatly expanding on her book’s characters’ lives and personalities, but also presenting a beautiful and realistic examination of a burgeoning relationship. It also boasted a fantastically diverse cast – including Charlie’s best friend Tao Xu, Tara Jones and her girlfriend Darcy Olsen, and Elle Argent, a trans girl who transferred to Truham’s all-girl counterpart school, Harvey Greene Grammar School for Girls.

While the Netflix adaptation of Heartstopper is, for the most part, an incredibly accurate adaptation of the graphic novels, retaining all that aforementioned sparkly dialogue – no surprise; Oseman is writer and executive producer on the series – the comic still retains its own identity. Now up to four graphic novels in print and still – at time of writing – ongoing as a webcomic, it offers an even more expansive exploration of the cast and their relationships, and allows Charlie and Nick’s relationship even more space to breathe.

Chiefly, this is down to Oseman’s use of page layout, and the visual tricks and flourishes comics allow that other media struggles to replicate. A particularly nice touch can be found in the earliest chapters, where Charlie explains a traumatic past relationship to Nick, displayed as text messages on a phone screen, accompanied by static images serving as a visual flashback. It’s a brilliant merging of prose and panel art, and although the TV show attempts to replicate the effect with floating text bubbles, the tone and emotion of the comic stands apart.

There’s also a fantastic use of silence – perhaps an odd element to highlight, but a potent tool in Oseman’s creative arsenal that’s used to magnificent effect in the comic. Multiple pages and entire scenes may be devoid of dialogue, yet still manage to pack in swathes of emotion. The adorable getting-to-know-you phase, with pages peppered with accidental finger brushes and too-long stares, the unspoken but growing attraction between Charlie and Nick, even Nick’s painful confusion over his own sexuality – all are brilliantly told without a speech bubble in sight. It’s a masterful use of visual storytelling, creating a sense of time and development in a way that only comics can offer.

It’s also worth fans of the show checking out the original comic for a slightly divergent version of the story. While the show brings forward the introduction of Elle, who doesn’t appear until the second graphic novel, it also lacks some other characters who are prominent in the comic – notably Aled, another friend of Charlie’s (and a major character in Oseman’s prose novel Radio Silence). The comic is also a slightly more authentic reflection of teen life in a UK high school – for one thing, Oseman is able to use more realistic, if coarser, language that the family-friendly Netflix adaptation tones down.

Ultimately though, a large part of the appeal of Heartstopper, both the show and the comic, is its optimism. While Charlie and Nick face obstacles on the path to true love – including questions of self-identity, peer pressure, family dynamics, and even, in later chapters of the comic, mental health struggles and eating disorders – there’s never any question that their love is real, or invalid, or “just a phase”. For older readers and viewers, Heartstopper is the queer romance denied to generations, an almost fairytale look at the stories that should have been available and the school experiences that should have been allowed but never were, while for readers the same age as the cast – the high school students in the here and now – it’s a joyous validation of young queer identities.

However, the best reason to check out the comics after bingeing the show is simply that there’s so much more of it. While Netflix has yet to confirm a second season of the show, if you’re left wanting more of Charlie and Nick’s sweet romance after the credits roll on the eighth episode, then Oseman’s original work is there for the reading, both online and in print.