How DoroHeDoro effortlessly presents strong women

Every once in a while, I get the urge for a dark, gritty seinen anime. And sometimes, as it did for me, that anime finds you unexpectedly. Enter DoroHeDoro. Based on the manga of the same name, the anime is a high-fantasy dystopian world, brimming with unconventional magic and surprisingly stunning, action-packed violence.

The highlight of my entire watching experience(s) were the women of DoroHeDoro. As someone who struggled to feel ‘worthy’ of watching anime growing up, the depiction of damsels in distress and overly-dependent young girls (who fawned and annoyed their male counterparts) played into my own condemnation of what I was told femininity was supposed to be. With the growing reclamation of femininity, and everything it is – and is not – I was forced to reckon with my own ideas of gender as an identity and a performance/expression. After becoming obsessed and scouring the DoroHeDoro fandom on TikTok recently, I found I wasn’t the only person unashamedly enamoured by Noi and Nikaido because of the stereotypical gender boxes they couldn’t be placed in.

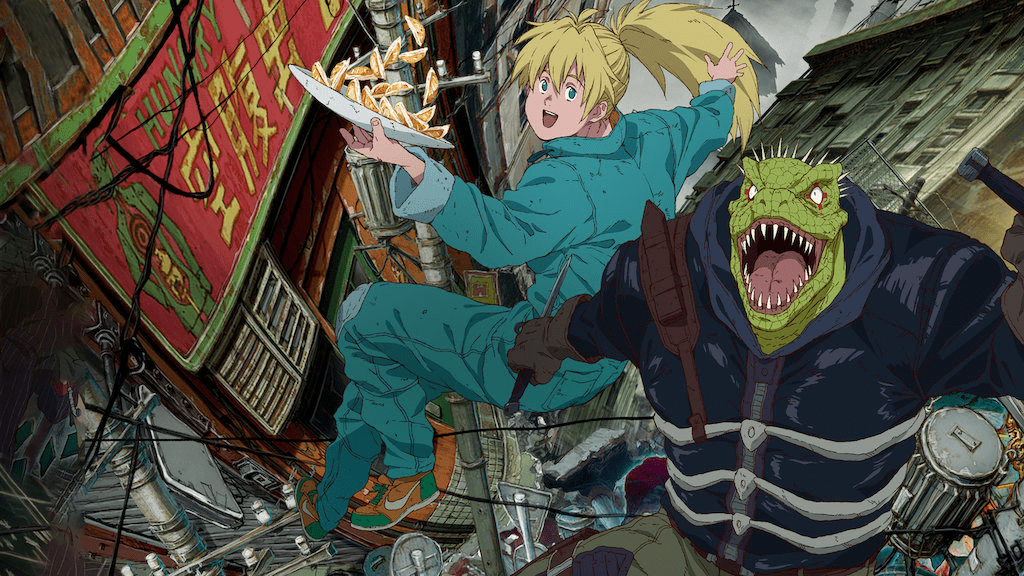

In season 1, we follow Caiman who, alongside his friend Nikaido, searches for the Sorcerer responsible for his lizard head. After a deadly confrontation, Caiman and Nikaido cross paths with one of the most powerful sorcerers, En. En sends two of his cleaners, Shin and Noi, to kill Caiman and embark on their search for the identity of the Sorcerer capable of the lizard-head curse as well. With a relatively straightforward premise, the striking animation, the whimsical worlds and characters, and the well-executed gore and violence become some of the undeniable charms of the series that makes this a must-watch seinen anime.

Seinen – a genre predominately marketed towards young men – is known to senselessly adopt cheap and sexual graphic acts against women. But in the world of DoroHeDoro, the women feel fully realised and complex; even in a relatively large cast, their stories don’t slink into the background, nor are they harmed for the spectacle of it.

The first woman we meet is Nikaido. She is first introduced as Caiman’s companion, helping him find the Sorcerer responsible for his lizard head. Her attire is a green jumper, usually buttoned-down, showing off her muscular and athletic physique. Most days, she runs her restaurant, the Hungry Bug, and whilst she is easygoing, she becomes ruthless in a fight. During the Night of the Dead episode, she takes a punch from Noi that sends her flying across the street and still manages to escape while carrying Caiman over her shoulders. Her body and physique never draw explicit sexual attention, nor is it truly commented on at all.

Similarly, Noi (who’s even naked at one point) is never sexualized by any characters, not even her male counterparts. In comparison to her partner Shin, Noi is bigger and more aggressive. Noi often wears a loose-fitting jumpsuit and a mask that conceals her features and is easily mistaken for a man. Outside of her jumpsuit, she is also quite busty, with a distinctively feminine face. Even in her sexier outfits – like the one she wears for the Blue Night Festival – it is played for comedy relief and not as a form of sexual appeal. When she is fumbling in her heels, mostly tripping over herself, her breasts don’t jiggle suggestively, nor is she landing in sexually suggestive positions. Instead, we have fun watching the sibling-type dynamic between her and her cousin, whose need for an extravagant affair forces Noi to wear heels in the first place.

Through Nikaido and Noi, DoroHeDoro does a great job of introducing fleshed-out female characters. We witness their stories and flaws and see them as 1-to-1 equals with their male counterparts, all without being subjected to stereotypical masculine traits. As a viewer, this was refreshing to see but also felt impactful. The response I had to these physically and magically powerful women was visceral. At no point were they defined by the constructs of femininity that I was used to seeing exploited in this genre. Even in this large cast, their stories are fleshed out. They are fully realised by themselves and as companions. Whether they’re fighting, bonding with their companions, or are sometimes suddenly nude, there is no shame or awkwardness in their actions, and there was no one there to police them on the expectations of their gender. In the sea of infantilized and ditzy, or sexy yet overbearingly annoying anime girls, these two women, instead, existed outside of the male gaze.

It isn’t hard to fathom the impact media has on its audience, including the fetishization of East Asian women and the perpetuation of unrealistic (global) beauty standards. The notion of art and life imitating each other isn’t a coincidence. For female-presenting people who want the room to participate in non-conforming gender expressions, shows with representation like those in DoroHeDoro shouldn’t go unnoticed. The media has its share of problematic depictions of characters who don’t conform to the gender binary, more than a few which contribute to harmful misconceptions. And, as with all forms of representation, this show instead serves to humanise people that look like them.

The demographic of global anime watchers grows daily, and though it is easy to lean on preexisting tropes for the sake of profit and familiarity, taking the time to represent the variety of this audience can only be beneficial. Although we aren’t short of strong women in anime, I can’t recall watching effortless portrayals of women with strengths, flaws, relationships, and ambitions that aren’t influenced by their gender or male counterparts like the women in DoroHeDoro. Audiences seeing these portrayals can benefit from dismantling gender stereotypes in the media they watch and the world around them.

Anime is inherently an experimental form of media that often plays with fantastical styles and aesthetics. With the many possibilities it already offers, the idea of deviating from typical gender norms isn’t unfathomable. It is the perfect avenue to show how fluid and adaptable gender can be. In the case of DoroHeDoro, women don’t have to, nor are they expected to, present themselves in stereotypically feminine ways to be valid in this world. Outside of my crush on Noi, the “validity” of her femininity never came to mind. There is something to be said about how exhilarating it was to experience the subtle and effortless depictions of strong women, as shown in DoroHeDoro.