Lesbian loneliness is portrayed perfectly in Life is Strange

If there’s something that we should take away from the portrayal of Steph Gingrich in the Life is Strange series, it’s that she represents something that’s rarely conveyed in media: lesbian loneliness.

Most media depicting lesbians, as those of us who secretively consumed every scrap of sapphic content they could get their closeted hands-on will know, focuses on romantic or sexual relationships. Our character might be getting over a break up, or entering a new relationship, or introducing a new girlfriend to friends or family. We already know that straight dudes think the whole point of being a lesbian is sex – as a performance for their consumption, to be precise – but it seems like the rest of us kind of think that, too. And if the point isn’t sex, then it’s definitely romance. What is a lesbian, anyway, if not reducible to a U-Haul joke?

I’ve been single for four years, and in that time I’ve gone on one date. That shouldn’t be embarrassing, but it feels like it. It shouldn’t make me feel undesirable, inadequate, or incomplete, but it does. And the more I think about how bad I feel, and how I shouldn’t feel that way, the worse it gets. There are plenty of reasons for that – most of which it’s my therapist’s job to listen to – but some of them are about culture. What I began to realise, in these four years, is that my entire sense of what it meant to be a lesbian was all about being with someone, or at least agonisingly wishing I was. But what is a lesbian, beyond pining? Who is a lesbian, alone?

Pop culture is pretty cut and dry on the subject. Even well-meaning discussions about what ‘counts’ as lesbian representation fuel this idea that there are right or wrong ways to see a lesbian, to be seen as a lesbian, or simply to be a lesbian. Many writers still shy away from using the word at all, and if they do it’s often in the most cringe-worthy or just plain lesbophobic ways. Even kinder texts tell us time and time again that lesbianism is something that has to be consummated. It’s a wanting, it’s a being with – it’s never simply a being. And ultimately this reinforces the logic of the systems of power we live in – it tells us we are not worthy if we do not achieve certain things or live up to certain norms. Worse, if we don’t want to, or realise we don’t need to.

This is probably especially true of video games, where lesbian representation is dominated by the dating sim genre, and the element of choice or action is a defining feature. Lesbianism is quite literally confirmed by the ability to choose particular kinds of sex or romance, and the rules of the systems that contextualise these choices: who you can sleep with or date, and on what conditions, depending on their gender and your own. If, as a woman or non-man, choosing women (and excluding men) is lesbianism, then choosing multiple genders is bi or pansexuality, and simply choosing no one is asexuality or aromanticism. And it might be, but not in my case. In my case, choosing no one is failing at lesbianism.

These were the sorts of feelings that were floating around my heart, but not yet in my head, when I first saw My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness on the shelf of my local comic book shop. It might have been love at first sight – if you believe in that kind of thing.

I know we’re always told not to judge a book by its cover, but sometimes a cover is undeniably compelling. This one depicted a naked woman, her hair about as frayed around the edges as her wide-eyed expression hinted she must feel. Her body turned away from the viewer, she half-looked at the other naked but faceless woman in the scene from across a bed that felt like a chasm, and half-looked back at me across the store.

It’s an arrestingly uncomfortable scene, dominated by a dusty shade of pink. That’s one of my favourite shades of pink – a colour I remember hating so much as a child because it felt like it represented the white, cis, heterosexual femininity I would never fit. I opened the book, and flicked through its pages before deciding whether or not to buy it. Probably this was just a pretense – part of me knew I needed this book as soon as I locked eyes with the petrified woman on the cover. Surely enough, that soft shade of pink – the colour of the sky on a particularly dreamy summer evening, or the colour of a schoolgirl blush – accented every page. A romantic shade of pink for an intimate encounter with the most un-romantic piece of lesbian literature I have ever read.

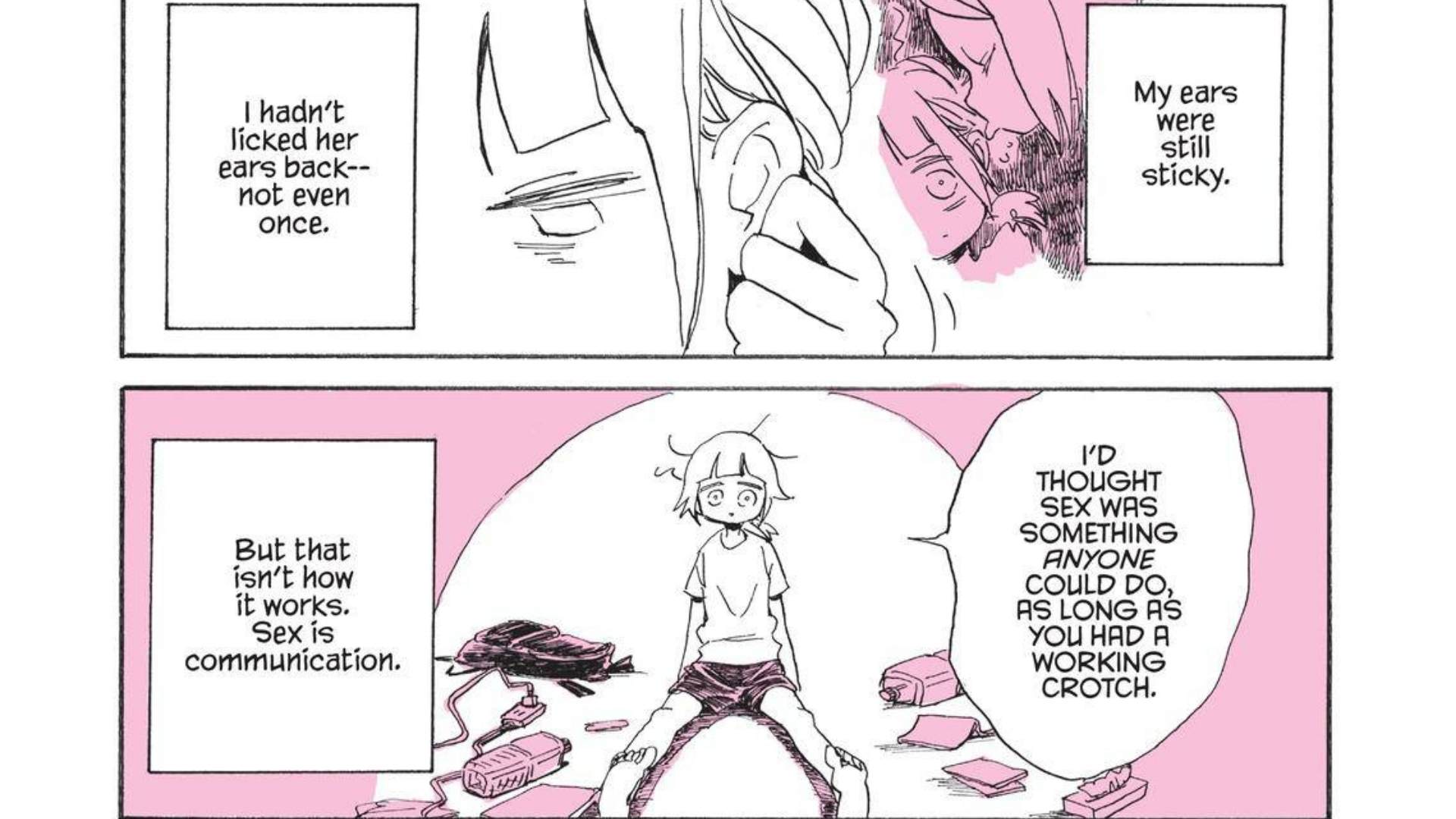

My Lesbian Experience of Loneliness opens with the most palpably unsexy sex scene. The faceless woman from the cover approaches Nagata Kabi, the author and protagonist, and all she can think about is the bald spot on her head and the scars on her arms. About to have sex for the first time, she is painfully aware of how her body bears the marks of her depression. She’s so afraid to be perceived by another person, because she’s sure they will affirm that she is as unworthy and unlovable as she thinks she is.

But this is not a story about a lesbianism that is a saviour. This is not a story about a love that cures depression. Kabi doesn’t walk away from that encounter feeling whole – like her lesbianism has been consummated somehow. Instead, this is a story about how gender, sexuality and depression seem to exist all at once, inside one another, indistinguishable. And as sad as that sounds, it’s also strangely comforting.

A few months later, I played Life is Strange: True Colors – a game that stirred something similar in me. It wasn’t quite the arresting, love-at-first-sight encounter I had with My Lesbian Experience, though maybe I’m looking back on that through rose-coloured glasses for your reading pleasure. This one crept up on me instead.

As deep as my love for the Life is Strange series goes – since I played the first game at 17 and realised that video games could, indeed, have gay people in them – never in a million years did I think I’d be comparing True Colors to my favourite manga. And yet, a few hours into the Wavelengths DLC, I suddenly felt like Steph Gingrich was looking directly at me from a TV screen, just as Kabi had looked from across the comic book store.

Wavelengths could reasonably be named ‘Steph’s lesbian experience with loneliness’. Not because these texts are similar in any formal, visual, stylistic or narrative ways, but because there’s a similar, recognisable emotional core to them. Kabi and Steph are both failing at lesbianism, right along with me.

Well, there is some need for pause here. Wavelengths ends – and True Colors starts – with the meeting of Steph and Alex. Whether Alex decides to pursue a relationship with her or not, Steph is evidently attracted to her. Is this the true consummation of Steph’s lesbianism? Was this story of loneliness just about the light at the end of the tunnel – about how loneliness comes to an end?

Maybe, or maybe not. I think Steph and Alex have an intimacy that should be cherished whether it’s a friendship or a romance. But here, right now, and maybe always, I am more interested in all the Stephs that leave Haven Springs alone. I’m interested in Steph the Fool, Steph the Hanged Woman, Steph the wandering weirdo. I’m interested in Steph the serial ghoster, Steph the D20-wielding fortune-telling agony aunt, and Steph the flakey lesbian punk nerd.

Steph and Kabi are both so afraid to be vulnerable. They are so alone and so uncertain. But they don’t need to be saved. There’s something undoubtedly powerful about the scene in Wavelengths where Steph finally stops avoiding Mikey, her best friend, the guy that knows her more than anyone else, and lets her sins spill forth. There’s something so radically vulnerable about the fact that Kabi shared with the world every thought, every experience of herself, her gender, and her sexuality that she thought she should be ashamed of.

Both texts offer a moving and tender exploration of lesbian characters in their isolation – not pining after anyone, as familiar as that gay experience is, but simply feeling alone. At the end of the day, every part of you exists all at once – you are a living, breathing creature in perpetual flux and motion, forever too fleshy and too complicated to be reduced to any one thing. Steph and Kabi’s lesbian experiences with loneliness make me feel like maybe there’s more to being a lesbian – and more to me – than sex and romance. When it comes down to it, maybe being a lesbian is just about being an entire, messy person.