Comics Corner – Why ‘Stuck Rubber Baby’ remains a masterpiece of gay comics

Get out the bunting and throw the confetti – it’s time to celebrate, as one of the greatest gay graphic novels of all time, Howard Cruse’s Stuck Rubber Baby, is finally back in print.

Originally published in 1995 by Paradox Press (a now-defunct imprint of DC Comics), Stuck Rubber Baby has flitted in and out of publication ever since. Thankfully, this month marks the release of the 25th Anniversary Edition from publisher First Second, a gorgeous hardback edition that collects the original 200+ page comic, plus photographs and unpublished archival material that explore Cruse’s creation of the masterpiece.

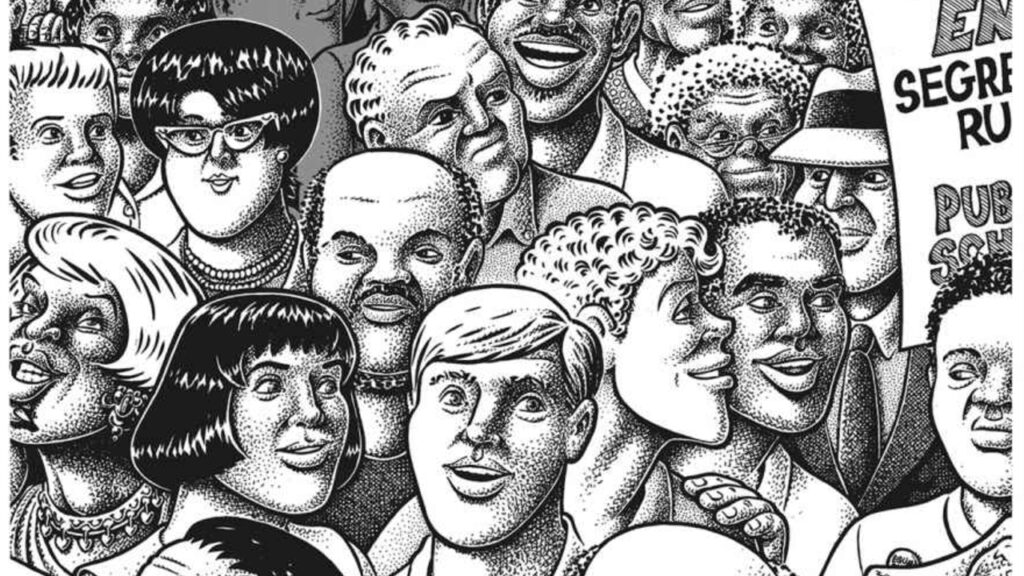

The story itself is a fictionalised account of Cruse’s own upbringing in the southern states of the US during the 1950s and ’60s, offering an unflinching look at the racism and homophobia of the day. Swapping himself for the young, directionless Toland Polk, Cruse uses the book to explore weighty issues such as internal battles with sexuality, trying to “go straight”, segregation, and the Civil Rights movement, all as the closeted Polk finds a warmer welcome in the Black community than amongst his white peers.

This is no ‘white savior’ text though – Toland is almost a passenger in his own story, working a dead-end job and getting carried by the tide of social upheaval. As Alison Bechdel – another iconic queer comics creator, and the same Bechdel behind the Bechdel Test – writes in her introduction to the 25th Anniversary Edition, ” This is not a revisionist fantasy in which the white hero flings himself wholeheartedly into the civil rights movement. Toland’s transformation is tentative, conflicted, alternately self-flagellating and self-serving—it’s a scathingly honest portrayal.”

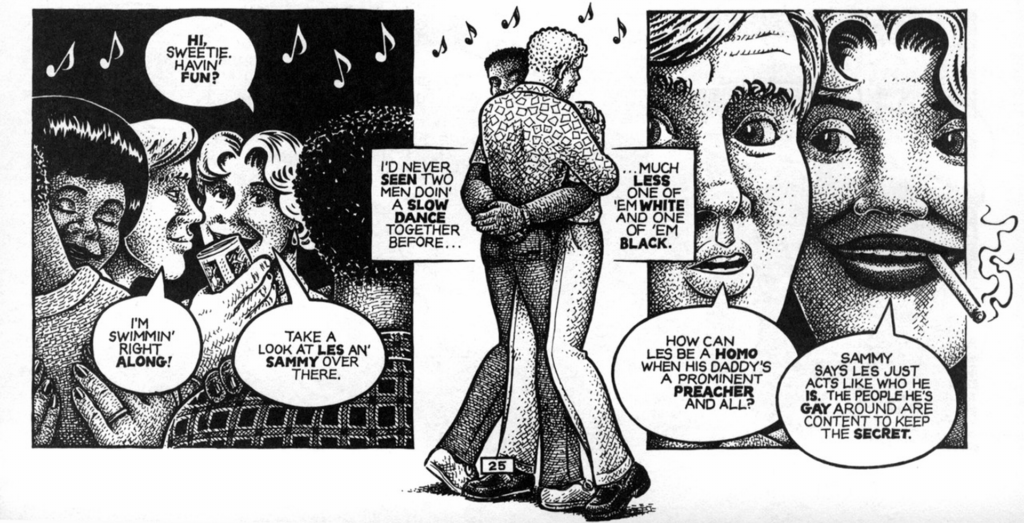

A key moment comes when Toland goes to an “integrated” party, one he’s tempted into by the promise of it being attended by “beatniks, anarchists, homosexuals” and more of mid-20th century America’s most unwanted demographics, including perhaps the most scandalous group of all: vegetarians. It’s here where Cruse, via Polk, observes two men slow dancing together – the first time he’s seen gay affection in public. Even more shocking for the time is that the two dancers are interracial, and the Black man, Les, is the son of a well-known preacher.

This opens a whole new world to Toland, but over the course of the evening he also meets Ginger Raines, a young white singer who’s already involved in the burgeoning civil rights movement. Still trying to maintain a facade of heterosexuality, he begins a relationship with her, one that morphs and evolves as he comes to terms with his own gay attractions – until he gets her pregnant (this echoed Cruse’s own youth, where he unwittingly fathered a daughter). Faced with difficult decisions over the fate of the child, yet still without any real drive in his own life, Toland’s life becomes increasingly complicated as he and his newfound community face mounting oppression.

Despite the title, Stuck Rubber Baby isn’t really the story of a young gay man accidentally becoming a father – or at least not just that. It’s an important text looking at one of the most crucial periods in the push for greater equality, for both gay people and the Black community. It’s a story that looks at the importance of community; of how the early gay rights movement was founded underground, with gays, lesbians, and trans people forced to live double lives; of how the roots of queer liberation are undeniably interwoven with the march for Black liberation. Although focused on the American South, the ramifications would be felt globally, something Cruse deftly touches on despite his protagonist’s broad sense of detachment.

Toland’s cluelessness, almost throughout the book, is also crucial. Although he slowly becomes more aware of social issues, he remains ultimately distant. Cruse is aware of the fact that, as long as Toland doesn’t ‘act gay’, he can still live a quiet life, never attracting the attention of bigoted cops or even the Ku Klux Klan. Les and the many other Black characters in the book, from Les’ parents to Marge and Effie, a lesbian couple who run a popular jazz club, are not so lucky – they can’t ‘act white’ and hide, as Toland can.

Stuck Rubber Baby was arguably ahead of its time when it was originally published in 1995. It dealt with issues such as gentrification and redlining – presenting them in plain language, such as characters observing that all the Black venues are on the poor side of town – and the problems they cause for communities of colour. These are ideas that are still only really beginning to gain any mainstream attention now. It also painted an unapologetically negative portrayal of police, presenting the force as almost uniformly corrupt, institutionally racist, and prone to raiding Black and gay nightspots with equal vigour and vitriol. The book’s publication came only four years after the assault on Rodney King, and it posed questions the world was – and perhaps still isn’t – ready to answer.

All of which makes Stuck Rubber Baby such an important comic to read now, in 2020. The issues it addresses remain urgent, even if the setting of the story is 60 years ago. It is, however, not an easy read. Its language is frequently offensive, using racial and sexual slurs with impunity given the setting. Even well-meaning white characters may use the ‘softer’ N-word, while the F-word appears with regularity. It’s a harsh and often shocking memoir on Cruse’s part, even with the fictional names applied to the cast. Despite the starkness of the material though, it remains a pivotal and illuminating graphic novel.

Stuck Rubber Baby is widely available in the US and UK. Please support independent bookstores!